|

George L. Garrigues , 1993

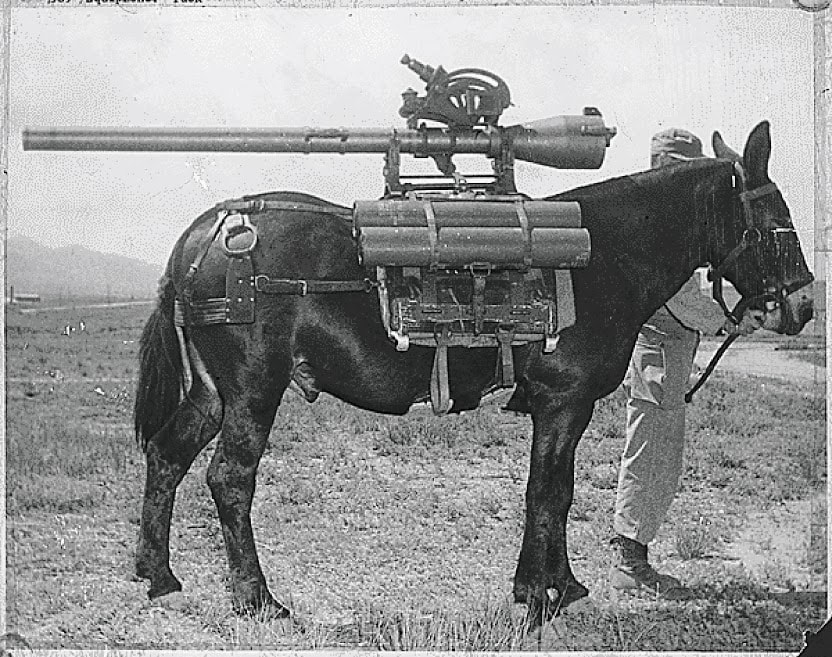

This is a reprint of an article from the 1993 Bishop Mule Days Program There are a lot of mule aficionados and Ervin A. Matthis of Redondo Beach is among them. This the tenth straight Mule Days that he has attended. While not a record by far, it is still impressive. Matthis gained his enthusiasm and respect for mules in Burma during World War II. He was a member of Merrill’s Marauders and the performance of army mules during that campaign proved their worth. He says, “A mule with a full pay load can go anywhere a man can on his own two feet. Mules can even pack their own weight for approximately a mile.” Matthis’ story begins at Fort Lewis in Washington and then goes on to Camp Carson in Colorado —training sites for army mules and the soldiers that taught them. The soldiers worked with the mules transporting normal loads using standard army stock saddles. However, some items required special equipment such as the pack saddle devised to carry the parts of the 1,500 pound 75 mm howitzer. This saddle consisted of a heavy steel frame over a thick leather cover lined with horse hair. It was fitted to the mules so that it transmitted the pressure of the pack to the part of the animals’ back best suited to bear the load. If a mule developed a saddle sore, the horse hair lining could be adjusted to remove the pressure from the sore area. Six mules were required to transport the complete howitzer. (Photos show the different parts ready to hit the trail.) This part of Matthis’ training included some high country terrain in Colorado. The soldiers, mules and their equipment were tested to full capacity. Even at that pace, their climb up and down Pikes Peak was not too big a challenge. Their next episode was a different story. The call for 3,000 volunteers including 100 mule skinners went out across the United States, Panama and the Pacific. It was 1943 and Ranger Unit 5307 Composite (provisional) was being formed for a long range penetration mission behind the Japanese lines in Burma. It soon became known as “Merrill’s Marauders.” From February to May, 1944, the Marauders participated in a drive to recover Burma from the Japanese occupants and clear the way for the completion of the Ledo Road to China. The Marauders were foot soldiers, their equipment transported by mules and a few horses that fought through jungles and over mountain passes in Burma. In five major and 30 minor engagements they defeated veteran Japanese soldiers. They prepared the way for allied advance into China. Matthis was one of the 100 who volunteered from the 98th Pack Artillery. They gathered in India. What followed could be called an ugly type of war. It was more a fight against geography, dank climate, mountainous terrain, matted jungle and disease than against the greater numbers or better weapons of the Japanese. Three hundred men remained in India as a rear echelon—their job to handle supplies and set up air drops for the men on the campaign. The other 2,997 men, 700 mules and horses started the hundred mile march up the Ledo Road to a point where it turned into Burma. Their first mission was to cut the Kamaing Road, a Japanese supply route. After successfully completing this assignment, “Merrill’s Marauders,” continued marching. From one mission to another, meaningless places to us, such sites as Tanja Ga, Shikau Ga, Nhpum Ga and Hsamsinyang, but all vital for the Japanese troops. The mule performance was extraordinary. They proved the benefit of their training. One was a natural leader. When headed up the trail, he followed it. The others fell in line, each behind the mule that he followed previously. Lines to keep them in place or moving ahead were unnecessary. They just moved along the trail doing their job, carrying their loads as expected. After more than 250 miles of jungle travel and combat, the troops had suffered the expected casualties. Mule losses were relatively low, although they were in a run down condition after carrying heavy loads with a minimum of grain rations. Top priority for the re-supply airdrops was ammunition and combat necessities. Men’s rations and grain for the animals were last on the list. The same applied to transport supplies on the mules. When a mule was lost, its load had to be distributed among the remaining animals. What they couldn’t carry was dropped. Grain was the first to go. The men carried their own rations on their backs. The mules were able to survive on bamboo leaves and the ground foliage, but the horses took longer adapting to the change in diet. Matthis comments, “Mules are not about to starve as long as there is something to chew on.” The fighting was fierce and physical exhaustion from seven weeks of marching through the mountains, jungles, mud water with insufficient food plus disease and nervous strain had drained the men and the animals. When they reached Nhpum Gu, one battalion was surrounded by the Japanese. It took almost two weeks to free the encircled men. During this fight, several pack animals were killed. After the battle, orders were received to capture the airfield at Myitkyina about 150 miles away. It was the only all weather air strip in Burma and vital to Japanese operations in that area. It was the beginning of the monsoon season and raining every day. The route followed a native foot trail over the Kumon mountains. It became almost impossible for the men and the heavily loaded mules, both in run down condition, to make it over the pass. Nevertheless, they started up the steep, slippery trail. Several slid off the trail and were lost –six in one slide, twenty in another. It was impossible to get some of the mules back on the trail, most rolled, 100-200 feet down the mountain side and had to be shot. At times the climb was so steep that the soldiers unloaded the mules and carried their loads. Sometimes lines were tied to the top heavy loads, snaked around a tree and, with the men pulling, the mules were able to make it up the trail. The end of the day brought sick call for the mules. The vet treated saddle sores as best he could and the horse hair in the pack saddles was adjusted to reduce the pressure. Regardless of its condition, if a mule could walk, he was loaded and ready to go at daybreak the next morning. Once the task of crossing the mountains was behind them, the men begun a forced march to the airfield. Going steadily for two days and one night, with only ten to fifteen minute breaks, they reached their goal. The mules kept up. After a hard battle, the airfield was captured. General Stilwell flew to it the next day to congratulate the victors. The airfield was more than an objective – it was the last hard core center of the Japanese in Burma. The victory effectively cut off the Japanese supply line into the Hukawng Valley and virtually eliminated the Japanese efforts in that area. This ended the tour of Merrill’s Marauder’s. Of the 2,997 men that began the campaign, 603 survived intact, the 2,394 had been wounded, killed or were disease casualties. This illustrates the difficulties, hardships and dangers that these soldiers and their pack mules encountered. At the termination of this action, the men returned to India and the United States. What happened after that is another story. Matthis’ last comment was, “This was one campaign where the mules proved their worth and played a mighty big part.”

3 Comments

Holly Subia

1/28/2021 12:58:47 pm

Many thanks to Ted Faye for sharing these pictures from his collection.

Reply

Frank Krone

5/28/2022 06:27:38 pm

Great summary noting the importance of the pack mules in WW2 as a necessary addition to the military weapons of war. In reading about the ratio of muleskinners to the number of mules assigned to specific units like Merill's Marauders, did the Army have backup plans in case a large number of assigned mule handlers were killed in battle?

Reply

1/9/2023 12:43:09 pm

Hi Frank,

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorAmerican Mule Museum: Telling the story of How the West Was Built – One Mule at a Time Archives

January 2021

Categories |