|

Video review by Holly Subia

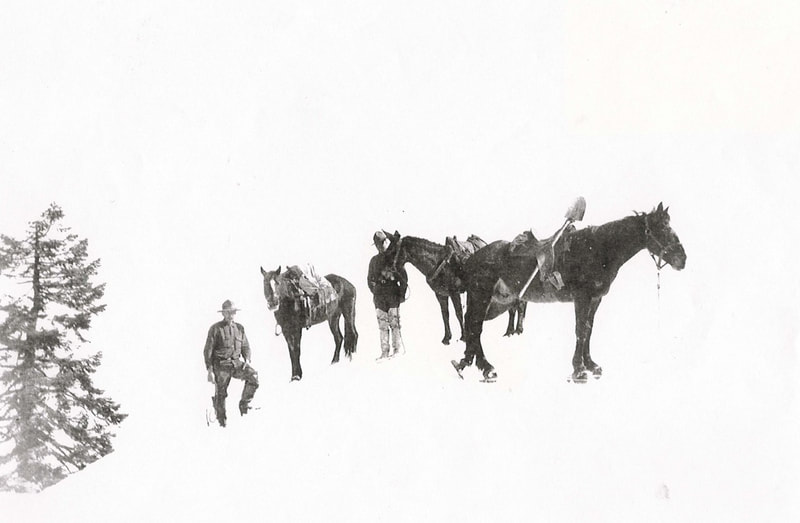

I recently watched a great video about mules on snowshoes. But to say it was just about mules on snowshoes is selling this video short. I also learned that any mule packing I did in the Sierra Nevada was amateur compared to what these men did. This video is called Bill Balfrey’s Mules on Snowshoes and made by Video Mike. You can find it on Mike’s web page under “Documentaries & Historical Subjects”. (https://video-mike.com/collections) The video starts with a presentation by Bill Balfrey where he presents and explains different equipment used by the team that packed mail and mining equipment into the mountains in northwest California. One of the pieces of equipment shone in the video is a snowshoe worn by the mules that helped deliver mail into the mountains during the winter. Each shoe was a square piece of wood and was usually about 10 inches square. There was some size variation with the different styles and who made the snowshoe. The wood of the snowshoes was treated with bees wax and boiled linseed oil to help preserve the wood and prevent the snow from sticking to the snowshoes. There was a slit in the wood where the mule’s toe would sit and two small holes where the mule’s heals sat. These holes were to accommodate the toe and heal caulks on the mule’s shoe. These holes, as well as a special metal clasp that went over the mule’s hoof, held the snowshoe in place. These snowshoes made it possible to take mules into the mountains, to carry mail, during the winter. Bill said they delivered the mail for about 12 to 14 years and only missed 2 days of mail delivery. Bill said they would train the mules to wear the snowshoes by gathering up the mules on a summer day and hold them all in the corrals. Snowshoes would be put on all the mules and the mules that figured out how to walk in the snowshoes worked the winter shifts. The snowshoes were just the first of many obstacles the mules learned to overcome during the winter. Hard packed snow would hold a mule in snowshoes but if the snow got to soft the packers would lay the mule on it’s side, put blinders on the mule and then slide the mule over the soft snow on a sled. Mules walked through deep trenches and tunnels dug into the snow and jumped down snow steps as high as 8 feet. Luckily the winter loads carried by the mules were mostly just U.S. mail. The mules did not carry such easy loads in the summer. During the summer these mules were used to pack all supplies needed at the mines located in the mountains. If one of the mines needed a tractor, the tractor was dismantled and packed in on mules. The tractor was then rebuild at the mine site. Because of the size and nature of these loads, most of them were top loads with little to no side loads. This in and of its self is a feat. These pack strings carried about 600,000 pounds a year. Each mule carried an average of 300 pounds but a mule could be asked to carry up to 600 pounds. A mule asked to carry a super heavy load was retired after they finished that trip. These pack strings worked until about 1920. This is just a short overview of the information in this video. I highly recommend watching this video if you get the chance. To see what these men and mules overcame to get their jobs done is truly humbling.

1 Comment

George L. Garrigues , 1993

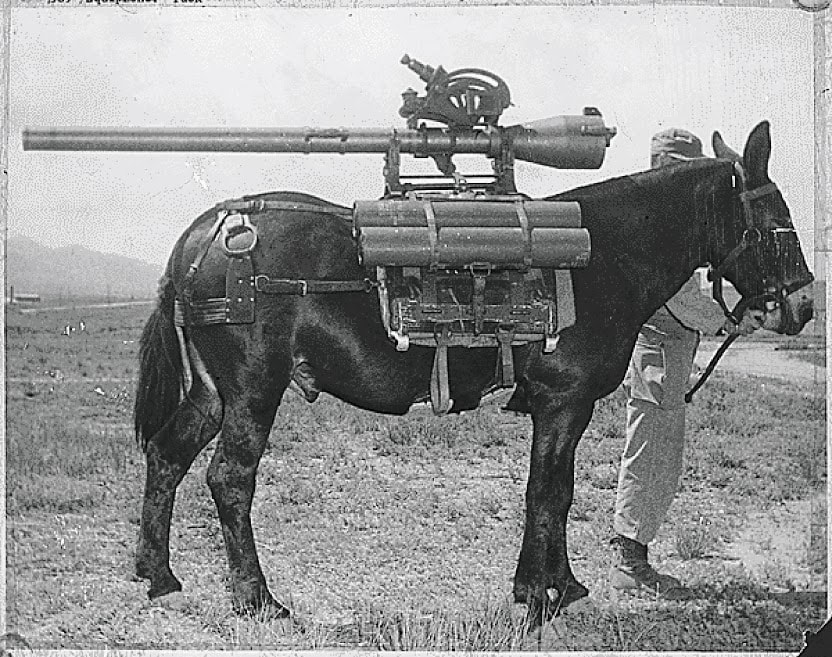

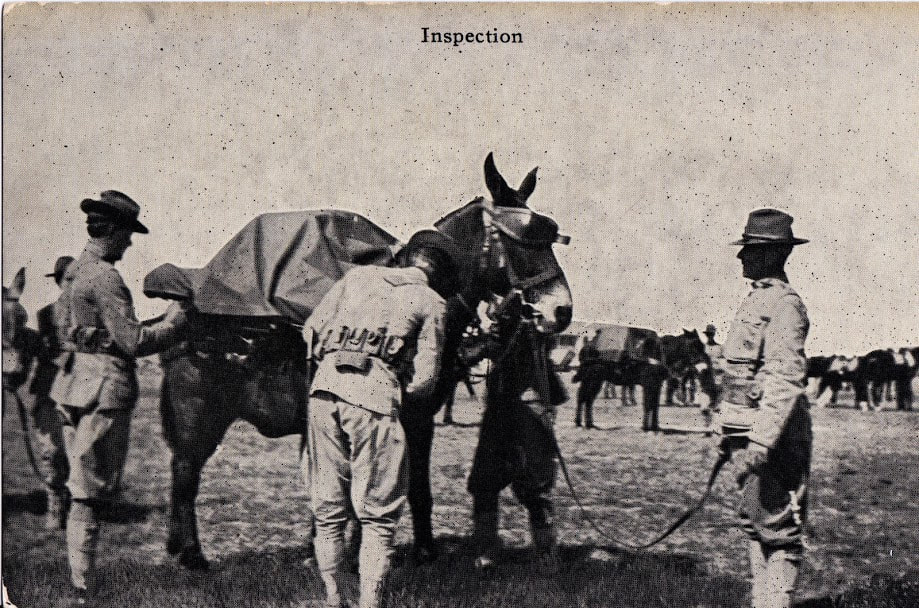

This is a reprint of an article from the 1993 Bishop Mule Days Program There are a lot of mule aficionados and Ervin A. Matthis of Redondo Beach is among them. This the tenth straight Mule Days that he has attended. While not a record by far, it is still impressive. Matthis gained his enthusiasm and respect for mules in Burma during World War II. He was a member of Merrill’s Marauders and the performance of army mules during that campaign proved their worth. He says, “A mule with a full pay load can go anywhere a man can on his own two feet. Mules can even pack their own weight for approximately a mile.” Matthis’ story begins at Fort Lewis in Washington and then goes on to Camp Carson in Colorado —training sites for army mules and the soldiers that taught them. The soldiers worked with the mules transporting normal loads using standard army stock saddles. However, some items required special equipment such as the pack saddle devised to carry the parts of the 1,500 pound 75 mm howitzer. This saddle consisted of a heavy steel frame over a thick leather cover lined with horse hair. It was fitted to the mules so that it transmitted the pressure of the pack to the part of the animals’ back best suited to bear the load. If a mule developed a saddle sore, the horse hair lining could be adjusted to remove the pressure from the sore area. Six mules were required to transport the complete howitzer. (Photos show the different parts ready to hit the trail.) This part of Matthis’ training included some high country terrain in Colorado. The soldiers, mules and their equipment were tested to full capacity. Even at that pace, their climb up and down Pikes Peak was not too big a challenge. Their next episode was a different story. The call for 3,000 volunteers including 100 mule skinners went out across the United States, Panama and the Pacific. It was 1943 and Ranger Unit 5307 Composite (provisional) was being formed for a long range penetration mission behind the Japanese lines in Burma. It soon became known as “Merrill’s Marauders.” From February to May, 1944, the Marauders participated in a drive to recover Burma from the Japanese occupants and clear the way for the completion of the Ledo Road to China. The Marauders were foot soldiers, their equipment transported by mules and a few horses that fought through jungles and over mountain passes in Burma. In five major and 30 minor engagements they defeated veteran Japanese soldiers. They prepared the way for allied advance into China. Matthis was one of the 100 who volunteered from the 98th Pack Artillery. They gathered in India. What followed could be called an ugly type of war. It was more a fight against geography, dank climate, mountainous terrain, matted jungle and disease than against the greater numbers or better weapons of the Japanese. Three hundred men remained in India as a rear echelon—their job to handle supplies and set up air drops for the men on the campaign. The other 2,997 men, 700 mules and horses started the hundred mile march up the Ledo Road to a point where it turned into Burma. Their first mission was to cut the Kamaing Road, a Japanese supply route. After successfully completing this assignment, “Merrill’s Marauders,” continued marching. From one mission to another, meaningless places to us, such sites as Tanja Ga, Shikau Ga, Nhpum Ga and Hsamsinyang, but all vital for the Japanese troops. The mule performance was extraordinary. They proved the benefit of their training. One was a natural leader. When headed up the trail, he followed it. The others fell in line, each behind the mule that he followed previously. Lines to keep them in place or moving ahead were unnecessary. They just moved along the trail doing their job, carrying their loads as expected. After more than 250 miles of jungle travel and combat, the troops had suffered the expected casualties. Mule losses were relatively low, although they were in a run down condition after carrying heavy loads with a minimum of grain rations. Top priority for the re-supply airdrops was ammunition and combat necessities. Men’s rations and grain for the animals were last on the list. The same applied to transport supplies on the mules. When a mule was lost, its load had to be distributed among the remaining animals. What they couldn’t carry was dropped. Grain was the first to go. The men carried their own rations on their backs. The mules were able to survive on bamboo leaves and the ground foliage, but the horses took longer adapting to the change in diet. Matthis comments, “Mules are not about to starve as long as there is something to chew on.” The fighting was fierce and physical exhaustion from seven weeks of marching through the mountains, jungles, mud water with insufficient food plus disease and nervous strain had drained the men and the animals. When they reached Nhpum Gu, one battalion was surrounded by the Japanese. It took almost two weeks to free the encircled men. During this fight, several pack animals were killed. After the battle, orders were received to capture the airfield at Myitkyina about 150 miles away. It was the only all weather air strip in Burma and vital to Japanese operations in that area. It was the beginning of the monsoon season and raining every day. The route followed a native foot trail over the Kumon mountains. It became almost impossible for the men and the heavily loaded mules, both in run down condition, to make it over the pass. Nevertheless, they started up the steep, slippery trail. Several slid off the trail and were lost –six in one slide, twenty in another. It was impossible to get some of the mules back on the trail, most rolled, 100-200 feet down the mountain side and had to be shot. At times the climb was so steep that the soldiers unloaded the mules and carried their loads. Sometimes lines were tied to the top heavy loads, snaked around a tree and, with the men pulling, the mules were able to make it up the trail. The end of the day brought sick call for the mules. The vet treated saddle sores as best he could and the horse hair in the pack saddles was adjusted to reduce the pressure. Regardless of its condition, if a mule could walk, he was loaded and ready to go at daybreak the next morning. Once the task of crossing the mountains was behind them, the men begun a forced march to the airfield. Going steadily for two days and one night, with only ten to fifteen minute breaks, they reached their goal. The mules kept up. After a hard battle, the airfield was captured. General Stilwell flew to it the next day to congratulate the victors. The airfield was more than an objective – it was the last hard core center of the Japanese in Burma. The victory effectively cut off the Japanese supply line into the Hukawng Valley and virtually eliminated the Japanese efforts in that area. This ended the tour of Merrill’s Marauder’s. Of the 2,997 men that began the campaign, 603 survived intact, the 2,394 had been wounded, killed or were disease casualties. This illustrates the difficulties, hardships and dangers that these soldiers and their pack mules encountered. At the termination of this action, the men returned to India and the United States. What happened after that is another story. Matthis’ last comment was, “This was one campaign where the mules proved their worth and played a mighty big part.”  Dear American Mule Museum, This morning I was talking with a friend. Somehow we had a conversation about anvils. So I sent him a picture of mine. I understand this anvil was used in a World War I mule team. A family member received it when the mule team disbanded. That is all I know about it. I was born in 1956 the year the last mule team went out of service. I was looking up some history and was surprised to find your American Mule Museum. I can't imagine anyone else in the world who would appreciate a picture of an anvil. Glad you're there. Be well, Scott Dear American Mule Museum, I have been a fan of the mule for many years now. Now that my beloved Betty the mule is gone, I have a desire to share her wonderful story with you. Enclosed is just part of our story prepared for your consideration and possible inclusion at your museum. If you are interested in more, I would be happy; to write more of her story, send pictures, prepare some video footage of our act on the circus and possibly also send her harness and props to your museum. I look forward to hearing from you, Sincerely, Dave Knoderer The American Mule Museum “The mule is often perceived and misunderstood as being stubborn, but more often than not, is simply smarter than the mule handler.” Betty the Mule Love at first sight Mules helped build America is an understatement. These sure-footed, calm and keen-witted animals were preferred over horses to carry packs up into rugged territory, skid boxes along chaotic shipping wharfs, pull wagons as part of large teams, drag a slip-scoop for an excavator and as riding animals assisting mankind for centuries. The true versatility of the mule was especially obvious when they were trained to entertain in the circus. During the winter of 1987, Dave Knoderer acquired “Betty,” the 12-hand jet-black mule as a baby. Pleased with her pretty head, pleasant disposition and animated trot, Dave began training her to perform at liberty, or completely loose – without restraints – in a circus ring. He also introduced her to the tricks of the ménage; lay-down, sit-up, bow, waltz, etc. for the sake of developing a comedy act. In her he found a willing animal easily enrolled and together they developed their own version of – the animal appears to defy the trainer – a comedy routine. From 1988 until 1990, as the wintertime student of John Herriott; liberty horseman, circus personality and trainer of all kinds of animals in Sarasota, Florida, Dave prepared his animals for circus performing. During those enlightening sessions, Dave rode “Souveran” the American Saddlebred while John rode “American Jubilee” his American Saddlebred. In addition to developing leg extensions, lateral movements and trick poses with their horses, John provided Dave with an understanding of how to start the hind-leg walk with Betty the Mule. During their nine-year career Betty and Dave - Gold-Dust and the Old Cuss - performed across American and Canada, in shrine circus performances, on traveling big top shows, as a rodeo attraction and at special events at nursing homes and educational assembly programs during a time when performing animals were falling from grace. Betty was always willing and attentive in the presence of others and especially kind to the children who adored her. Taking advantage of one last opportunity to perform for fourteen weeks in the summer of 1996, Dave performed two circus acts twice a day; “Souveran” the Haute E’cole or high school dancing Saddlebred horse, and “Betty” the liberty, ménage, trick and comedy mule at the tourist attraction called the Circus Hall of Fame in Peru, Indiana. During her career as “Gold Dust and the Old Cuss” Betty delighted audiences across all of North America. Then she retired as a beloved member of the family. Betty lived to the age of 34. Be Good, Be Well, and Ride Safe Dave "Letterfly" Knoderer Jesus Triumphal Entry

Story narrated by the Donkey Submitted by Jennifer Roeser, edited by Holly Subia Hi everyone, my name is the colt of a donkey. I am the donkey Jesus rode at his triumphal entrance into Jerusalem the week before he was crucified. Oh how thrilling it was to have the master, the King of Glory chose me, to carry him into the Holy city. What an exciting time. Thousands of years before god created the earth, Jesus as the Word of God knew he would die on the cross. Wow! You know what else? He also knew he would choose me, the colt of a donkey, to ride on. So, you know what he did? Since Jesus is the creator of all things and knew he would die on the cross, when he created the donkey he put a cross on ours backs as a symbol of his death and resurrection. Oh, and when Mary was going to Bethlehem to give birth to Jesus she rode a donkey to the manger. Mangers are where the animals are stabled. So we donkeys got to see Jesus be born! Then, that very night, shepherds came to visit the newborn King. The shepherds told us that all the angels of heaven appeared to them and said, “Today in Bethlehem, a Savior was born, Christ the Lord. And all the angels sang, “Glory to God in the Highest, Peace to all Men." There is a story on the Internet called, “The Legend of the Donkey Cross" by Mary Singer. It is a poem she wrote about me. The story is not exactly how is happened but it is how I feel about my Lord. I am so elated to share my story with you. Thank you, Merry Christmas and Happy New Year. Ms. Horse, Ms. Mule and Ms. Cow — a Christmas fable

Posted by Dave Tabler https://www.appalachianhistory.net/2018/12/ms-horse-ms-mule-and-ms-cow-christmas.html Ms. Horse loved to eat hay, especially fresh hay. Well, before long, baby Jesus would be laying on the hard boards of the manger and wake up cranky and yowling, like any little baby. Mary would say, “Now Ms. Horse, stop eating that hay! You’re upsetting the baby.” Mary would then fetch some more hay for a mattress and baby Jesus would go back to sleep. As soon as everybody had their backs turned, Ms. Horse would sneak over and snack on some more hay and the whole problem would start again. Baby Jesus would wake up wailing. Mary would lecture Ms. Horse, and Ms. Horse would lower her head and look real remorseful, you know, real sad. As soon as no one was looking, Ms. Horse crept over and nibbled on the hay until baby Jesus was laying on those hard boards. Well, it didn’t take long, Mary got a little bit nettled, you know, kind of mad like, just like the rest of us. Mary said, “Ms. Horse, from now on, you and all your kith and kin and all your children’s children will never get enough to eat. You will have to eat all the time.” Have you ever seen a horse out in the field? They are eating all the time. If you ever own a horse you will understand. When you own a horse you are feeding them all the time. Ms. Mule also was naughty in the barn. First, Ms. Horse was eating up the hay mattress and waking up baby Jesus. Next, every time baby Jesus fell asleep, Ms. Mule would go “Hee haw! Hee haw!” Let me tell you, you have never heard a baby cry, until you hear one cry after a mule goes “Hee haw, hee haw.” Oh my, how Mary would speak to Ms. Mule. I was told that almost every time the barn would get quiet, Ms. Mule would start in, “Hee haw, hee haw!” She’d wake up baby Jesus from his nap and he’d start in crying. Ms. Mule was so loud, even the grown ups would jump. Mary got so aggravated, she said, “Ms. Mule, you are not fit to be a parent! From now on, you and all your kith and kin will never become parents!” Do you know, to this day, no mule has never had a baby. Now Ms. Cow, she was different. Ms. Cow was something else. Yep, she sure was. Ms. Cow was a big help to Mary in that barn. For example, Ms. Cow would stand with her back next to the manger and wave her tail back and forth over baby Jesus, to keep the flies off him. There were lots of flies in that old barn. Ms. Cow gave fresh milk, to both Mary and Joseph, and to some of the other visitors to the barn. She and Jack, the Donkey, would take turns babysitting whenever Mary and Joseph had to run an errand. Ms. Cow also told Jack what a lot of the things were called he was seeing for the first time, since the miracle of the “First Christmas Gift” when Jack got his sight. They were the best of friends. Later, when Mary was packing up to go down to Egypt, she said, “Ms. Cow, you have been such a helpmate to me and baby Jesus, I want to thank you. From now on, you and all your kith and kin and your children’s children, whenever you finish eating your lunch on a warm summer day, you can go lay down in the shade of a tree and continue to enjoy your lunch with a chew of grass.” The next time you see cows out in a pasture after lunch laying in the shade, you will see them chewing away like they had a big wad of chewing gum. The farmers say the cows are chewing their cud. Yep, that’s why horses always eat, mules don’t ever get to be parents, and cows get to chew their cud after dinner. Chuck Larkin, Chuck Larkin (1932-2003) was a nationally known folk storyteller who lived in Atlanta, GA. A “tall tales anecdotist” and a scholar of Celtic lore, he also conducted Master Storytelling Workshops. Larkin was a charter member of the Southern Order of Storytellers, and often attended the National Storytelling Festival held in Jonesborough, TN. Burma was lost, said General Alexander, “because mechanization was sent when animal transport should have been used. There were only two main roads in all of Burma.” This is the same General Alexander who was directing field operations of British and American Forces, under General Eisenhower, in Tunisia. Alexander commanded British troops in Burma. War is the most practical thing on earth! Man hasn’t yet made the machine that will replace the foot soldier or the pack mule. Terrain and weather still dominate the battlefield. When the going got tough in Tunisia: when food, ammunition and even water were needed by troops in position where trucks could not reach them; when fog enshrouded planes and jeeps spun in the mud, the pack mule was brought into action—Yes, 2,000 of them were reported by the press. And more important, mule pack trains supplied oil, repair parts and gasoline to stalled tanks, by routes wheeled vehicles could not traverse. Normal supply routes were destroyed or blocked by enemy fire. And tanks, like cavalry, cannot be tied to supply routes. Supply must reach out and deliver. The tactical combination of armored with other forces, in a swiftly moving campaign is difficult, but the greater problem is supply and transport at the speed and range that are necessary—and the vaunted jeep has no place where the going is steep. War Department radiocast of the Bureau of Public Relations, 3 April, 1943, stated: “the territory in which Americans in Tunisia have been fighting in so rugged, so wild, that even Jeeps cannot navigate the hills and so the American Army is being supplied by mule trains.” In a recent test in the high Rockies at Camp Hale, Colo., between Jeeps, Ski troops and Pack Mules the mules won, with the Jeep first out, blocked by snow. Where motors can’t go, pack units will flow. The pack mule can go wherever a man can go, with the use of his hands. The Press reports “long lines of mule trains are common sight in New Guinea.” Pack artillery is the artillery weapon for the jungle and the mountains of the tropics. Germany transported pack artillery by plane to Narvik, Norway. Italian mechanization failed in winter warfare in Greece, but Greek Pack Artillery climbed the mountains and plowed through the snow. Russia could not use its motorized equipment in winter, and Japan’s mechanization, due to mud and narrow mountain passes, failed in China. With the Chinese fighting desperately, but without artillery, the Chinese Mission appealed for a packsaddle to 75 mm artillery on the small 800 pound Mongolian ponies. Thousands of these sturdy ponies are packing American 75 mm. Howitzers on specially designed Phillips’ saddles—to the distress of the Japanese! Three plants are engaged in the production of the saddles. Press dispatch of 3 June, 1943—‘”The Chinese battle of Stalingrad’ was fought around Shilpei! The Japanese were unable to use their tanks and big guns in the mountains. They suffered about 30,000 casualties.” Chinese pack artillery had moved through and around the narrow passes and used their American 77 mm Howitzers with telling and deadly effect. The Tokyo Gazette reported: “The usefulness of the horse in modern warfare is one of the discoveries of the present conflict, particularly in battles on the rugged steeps and in the narrow passes of the Chinese Mountains.” The essential clue to success in modern warfare is a balanced load force of all arms, with the necessary teamwork between its component elements, plus a commander who has a really sound knowledge of the mechanism of the war—i.e. topography, movement and supply, with supply the greater problem. The Phillips’ Packsaddle won its place in the world by competition with the packsaddles of the principal military powers. The saddle also won first place in tests conducted by the Army Service Boards, winning each of three 500-mile marches conducted by Pack Artillery Boards. No other piece of Army equipment ever won such recognition. Over 75,000 of these packsaddles were made in the last three years. Phillips’ Packsaddles are in use in all parts of the globe, where United Nations troops are fighting, and also in many friendly Allied countries. Twenty thousand mules were purchased by the Army in the last eight months—while only 2,000 were purchased by all buyers in 1940. The fact that roads are blasted both by artillery and bombs, and that mines are planted along normal routes, makes it all the more important that supply pack trains and pack artillery be made a part of military forces. Where packsaddles are necessary, all other matters are secondary. Col. Albert E. Phillips Army Navy Journal, July 24, 1943 Mule Days program --1987 Many thanks to Ted Faye for sharing these pictures from his collection.

In the June 6, 1975 issue of the Los Angeles Times, Outdoor Writer Lupe Saldana wrote the following observation on Bishop Mule Days, then celebrating its sixth birthday: “A new celebrity is emerging in the equine world, the lowly mule. Its sudden popularity for riding, racing and packing is making it a high-priced, highly prized animal. The price of a good mule has tripled lately, with selling a previously unheard-of price of $6,000. A few years ago these ‘diamonds in the rough,’ as one packer calls them, sold for $200 to $400 with few takers. Now the asking price is $600 to $1,000 with lots of takers. Members of the horsey set started saddling up mules as a lark about five years ago, and now the fad has caught on. Mule experts estimate that the riding of mules for pleasure has increased more than 10 times since 1970. Part of the credit for the new interest in mules goes to the Chamber of Commerce of Bishop. Its annual Mule Days celebration is the leading Southern California showcase for the old-time beasts of burden. This folksy event staged at Bishop at the foot of the High Sierras started as a hometown happening in 1970. This year it showed signs of becoming a national attraction. A parade down Main St. over the Memorial Day weekend drew 20,000 people. All motels were sold out, and record crowds jammed the Tri-County Fairgrounds for the three-day program. The big events were mule racing, reining, packing and shoeing. Mules come in all sizes and colors, depending on the parents. They are the offspring of a male ass and female horse. Horses from ponies to Percherons are used. The mule has long ears, a short mane, small feet and a tail with a tuft of long hairs at the end. From the jackass it gets its ability to conserve strength, work hard for long periods, carry heavy loads, be sure of foot – and be stubborn. One thing that tends to hold down the price of mules is that both males and females are sterile. On rare occasions, a female mule bred to a male ass or stallion has produced an offspring. Mule Days are conceived by Bob Tanner, a Sierra packer for 26 of his 45 years, as a way to get publicity for the slumping packing business. Glorifying mules was a byproduct. ….fifty mules were entered in 1970 events and this year there were 300. Entries, once mostly locals, this year came from Texas, Colorado, Idaho, Oregon, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, and many parts of California. ….What attracted the visitors? ….A college student from Riverdale, near Fresno, gave a typical answer: Mules are something special. They’re twice as smart as horses. That’s why it takes twice as long to train them.’ (He) said that because mules are so smart they refuse to immediately buckle under to man, but when they do come around they are superior to horses. Others like mules because they are hardier than horses, easier to care for than horses, and make better pets and work animals. Packers have always favored mules for backcountry carrying work because they are surefooted, carry heavy loads and are easy to keep in feed because they aren’t finicky what they eat. They say it is impossible to overload a mule because if the animal feels overloaded it won’t budge. There’s no comparison in longevity between mules and horses. Some mules are hearty at 30, living to 35. Horses are old at 15. Critics say mules are treacherous and difficult to control. “That’s true,’ a packer says, ‘but they aren’t born that way. They’re made that way. They’re smart and they won’t stand abuse. Treated with respect, they are worthy friends and loyal servants.’ Newcomers are advised that to successfully handle a mule a person must be firm and never show fear. The mules and merchants aren’t the only ones who get a boost from Mule Days. The winner’s circle was dominated by women, who use skill rather than muscle to control their mules. ….Denton Sonke, manager of the Bishop chamber, says the women dominated the events ‘because they’re dedicated. ‘They spend lots of time training and riding their mules. The boys spend most of their time with hot rods.’ The mule business appears to have a bright future because the increase in prices has encouraged breeders to use thoroughbred mares. In the past the least desirable mares were used for breeding. And Tanner says Mule Days has a big future ‘because this is a different kind of show…You never know what’s going to happen with a mule.’ “ Photos from 1975 printed in the 1976 Mule Days program.

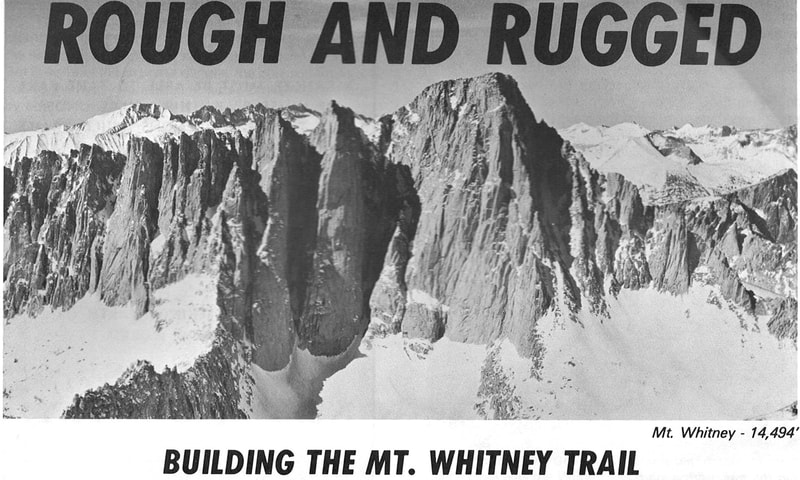

Building the Mt. Whitney Trail

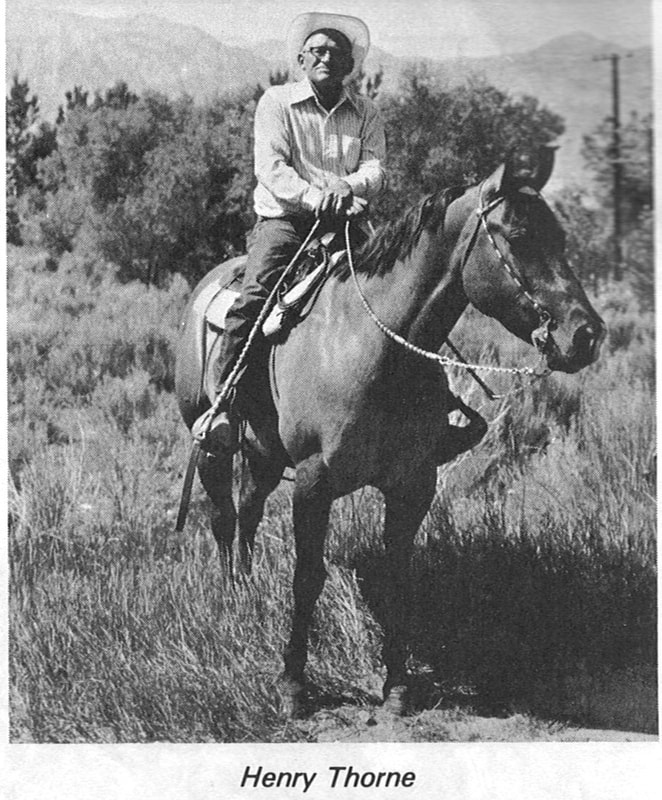

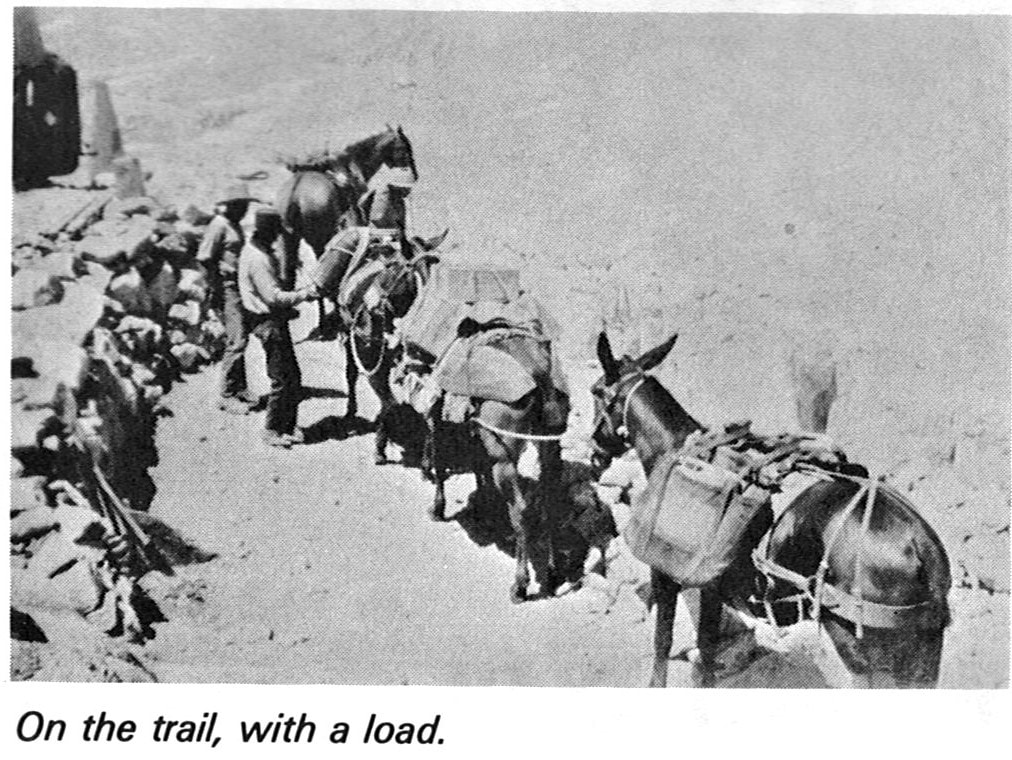

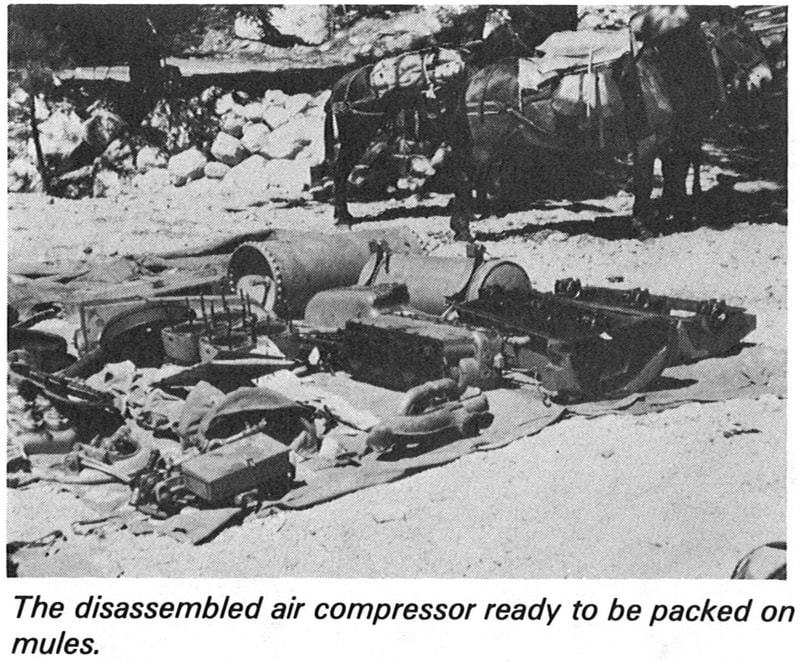

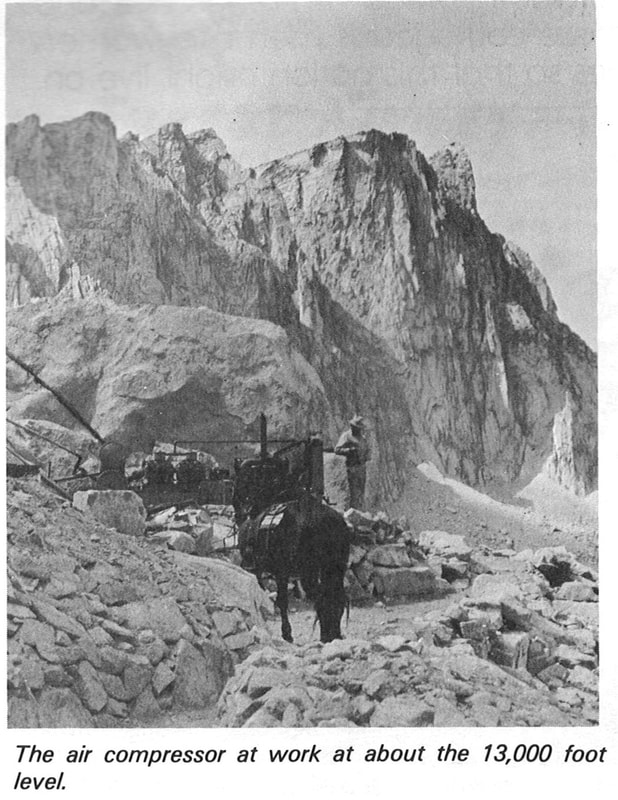

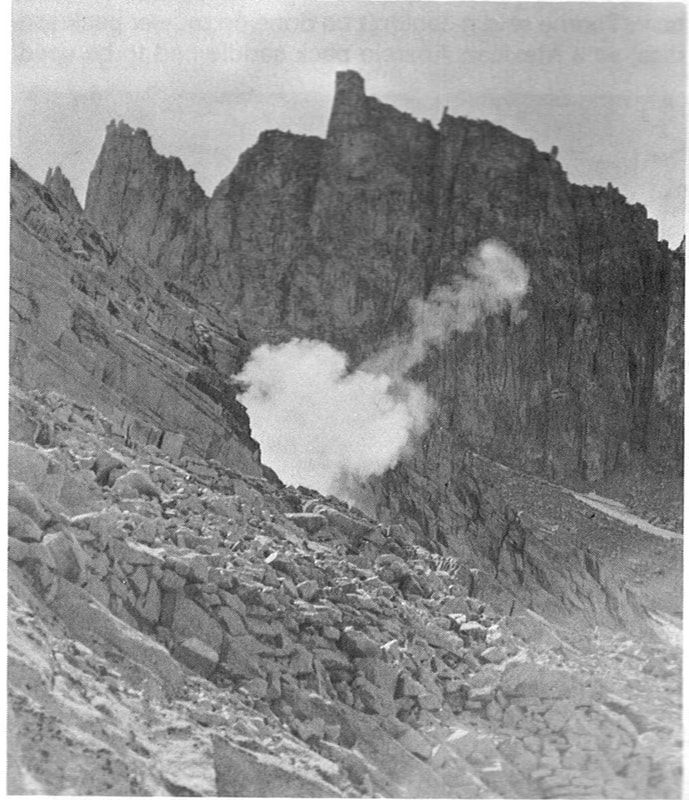

Each year thousands of hikers climb the strenuous trail to the summit of Mt. Whitney, but few realize the vital role the hardy Eastern Sierra packers---and their surefooted mules---played in building the steepest portion of that scenic trail. Henry Thorne, the acting forest engineer in charge of construction for the Forest Service at that time, said the task couldn’t have been done with them. Mules played an integral role in the building of many trails, as well as maintaining more than 700 miles of trail. But Thorne says none of them were as difficult as the portion of the trail from Consultation Lake to Whitney Pass, which includes the well-known 96 switchbacks. In order to avoid deep annual snow drifts, it was necessary to re-route part of the Whitney trail to wind back and forth up the side of a sheer granite wall. This task was begun in July of 1947 when the Mt. Whitney Pack Train at Whitney Portal was contracted by the Inyo Forest to both haul heavy equipment to the 12,000-foot trail camp, and then to keep the hard-working crew supplied throughout the summer season. Drilling cuts as deep as 36 feet into solid rock to make the Whitney trail wide enough was a major job that necessitated the use of an air compressor, which weighed a hefty 10,000 pounds. This Schramm compressor had to disassembled, small pieces carefully packed onto mules for the long journey to the new trail site, and then reassembled. Thorne said the heaviest piece was a crankshaft, which weighed some 344 pounds and was carried on one mule. In addition to packing the heavy air compressor up the mountainside to drill into rocks, some 1,500 feet of pipe had to be packed up the trail. Air was then piped up the mountain to operate the compressor. Packing heavy equipment on mules was no easy task. Thorne said it couldn’t be done on regular pack saddles, so a Mexican Aparejo pack saddle had to be used. Using these saddles required skills and expertise that the early packers had mastered, making them especially valuable in the transport of heavy equipment up the steep slopes. Once the air compressor and piping was packed up the mountain, the mules became a vital link to the outside for supplies of all kinds: groceries to feed the hardworking crews, wood to keep their tents warm on cold nights, dynamite powder to blast through the hard rock, and much more. Thorne recalls that packing the heavy equipment took about four strings of five mules each, and then one string was used to service the camp almost daily. “If it hadn’t been for mules, the whole job couldn’t have been done at all,” said Thorne. “This country never would have made it without them old mules. That’s for sure. “And I don’t think anybody could ever find a better bunch of people to work with than the packers on the Eastern Sierra because they were always cooperative, they always helped,” he added. “They wanted the work done, and they’d go all out to help you.” The packers were also extremely helpful to Thorne who worked for the Forest Service for more than 30 years before retiring in 1963. “I’d worked lots of mules in the Mid-West,” he said. “But they had the load behind them—not on their back. So I had to learn a lot when I came here. The packers were helpful in teaching me. What I know, I owe to them. The 12-man trail crew was a hard-working, hardy bunch who were supervised by Relles Carrasco. Equally important was Carrasco’s wife Lizzie, the famed cook. “They were a great crew to work with,” Thorne recalled. “They never asked about the pay. They asked if Lizzie was cooking. Lizzie was an awful cook.” The job took two seasons to complete, and it was often times a hazardous task. The men, while drilling on the side of a steep bluff, were held by ropes for safety. But in spite of the extreme danger, the only serious injury during the heavy construction was a broken leg suffered by one of men due to a rock slide. In July of 1948 the final phase of the Whitney job was begun and on Sept. 8, the first group to the completed trail was the Wilderness Riders of America accompanied by Forest Service personnel and members of the Mt. Whitney Pack Train. Thirty-five people with their pack and riding stock used the trail this first day. Before completion of the new trail, about 200 people used it over a busy weekend. In recent years a quota system was enacted to protect the environment from overuse, and now 75 people are allowed up the trail each day to climb Mt. Whitney—the highest mountain in the continental United States. Rebecca Cheuvront 1986

by Holly Subia It is no surprise, and well known, that people used mules to haul heavy loads long before they had large tucks. And the “Mac Truck” of mules came from France. The Poitou mule came from two distinct parents. The sire was the Poitou jack, the largest donkey breed in the world. The Poitou donkeys are known for their long dreadlock like coats and their large size. They can get up to 16 hands in height. The dam is a Poitevin mare. Poitevin horses are a large, heavy draft horse used throughout France in agriculture and other draught work. The Poitou mule was sought after the world over, known for it’s strength and gentle nature. The mules were often 17 hands heigh. The demand for these mules was so high a Poitevin mare would usually have one horse foal and then all other foals would be mules. The mules were used in agriculture, freighting and in the military. But after World War II and the industrial age, all three breeds where no longer in such demand and saw a huge reductions in population. The Poitevin region of France once produced around 19,000 mules a year. The annual average of Poitou mules born now is 20 a year. All three breeds, Poitevin horse, donkey and mule are considered endangered breeds. There has been a process but in place to evaluate Poitou donkeys that are not pure bred. If the donkey passed the evaluation it will be included into a breeding program to increase the population of Poitiu donkeys. Today, Poitevin mares will often only have one mule foal in a lifetime. Mares are in a 4 year breeding rotation with stallions. This is to reduce inbreeding and have foals that are not related. These foals will produce the Poiteven foals in the future. The Poitou mule might have to be in decline for a while to assure strong foundation stock for the future. Mules are lucky creatures; they can go extinct but as long as we have horses and donkeys we can make more mules. |

AuthorAmerican Mule Museum: Telling the story of How the West Was Built – One Mule at a Time Archives

January 2021

Categories |