HISTORY OF THE JOHN MUIR TRAIL

by Marye Roeser

In the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range of California, cattle and sheep ranchers were largely responsible for many of the trails throughout the range. Most of these trails were not specifically constructed but rather just happened in moving livestock to and from the mountains for summer grazing. Occasionally, the sheep and cattle herds followed old established Indian Trails.

The U. S. Cavalry monitored Yosemite and Sequoia Parks before the National Park Service was organized, and in so doing, they cleared and improved existing trails. When necessary, army soldiers constructed new trails in order to better access a destination. These trails were all passable by horseback and pack mules. Everyone rode horses or mules and only hiked to reach a locality not accessible by riding animals.

Towns on both sides of the Sierra Nevada financed trails to access destinations and private entrepreneurs built toll trails. Local livery stables provided horses, pack mules and guides.

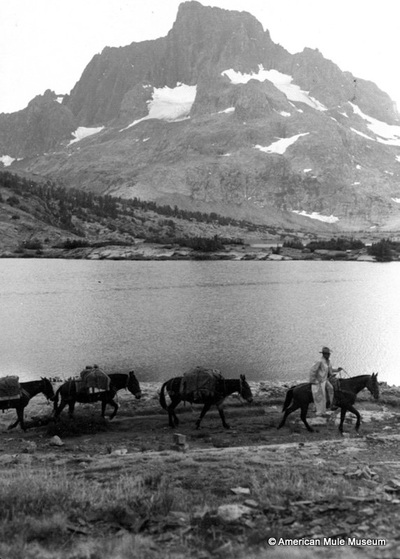

Theodore S. Solomons, a charter Sierra Club member, conceived the lofty idea for a high trail along the backbone of the Sierra Nevada between Yosemite and Mt. Whitney. He thought the north to south high trail should be as near to the main crest as possible. From 1892 through 1897, Solomons made many extended pack trips of exploration, principally in the upper branches the San Joaquin River system. His concept of the route required that the trail be passable by saddle and pack stock. Solomons was later helped in his explorations by Joseph N. LeConte (Little Joe), a professor of Engineering at UC Berkeley and Bolton Coit Brown, a professor of drawing at Stanford University and his wife, and Walter Starr, Senior. Their writings and detailed maps, contributed greatly to the overall knowledge of the High Sierra. Walter Starr later finished and published, The Starr’s Guide to the John Muir Trail in 1934. His son, Walter Starr, Jr. had written the manuscript for the book before being killed in a fall while climbing in the Minarets. This book is still the manual for travel in the Sierra.

In 1914, John Muir, who was president of the Sierra Club, died unexpectedly. Club members searched for a lasting way to honor him. Meyer Leissner, came up with the idea of naming this same proposed north to south high trail after Muir, calling it the John Muir Trail. The Club formed a committee to work with the State of California to acquire funding for trail construction. The committee consisted of: Meyer Leissner, Chairman, Walter Huber, David Barrows, Vernon Kellogg and Clair Tapaan. The State Engineer, Wilbur McClure, looked at the various trail options and selected a route that was mostly the route laid out by Solomons and LeConte.

The State of California allocated $10,000.00 to begin construction in 1915. McClure negotiated with the newly organized Forest Service to manage and supervise the trail work with the State furnishing the funding. In 1917, the State again voted to appropriate another $10,000.00. There were 3 more additions of construction money from the State – in 1925, 1927, and 1929. Due to the Great Depression, the State of California could not contribute any further funds. The National Park Service (that had been established in 1916), jointly with the Forest Service, funded the remaining trail construction.

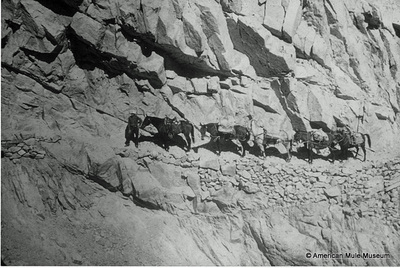

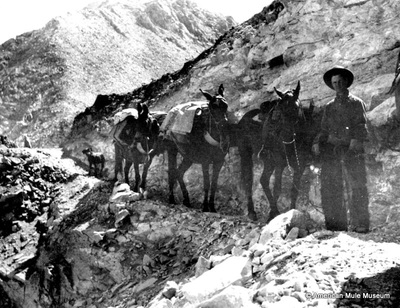

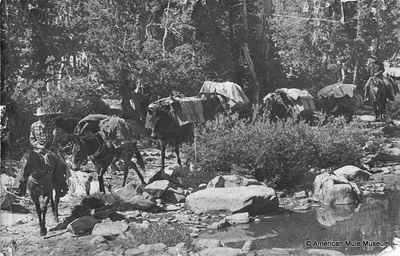

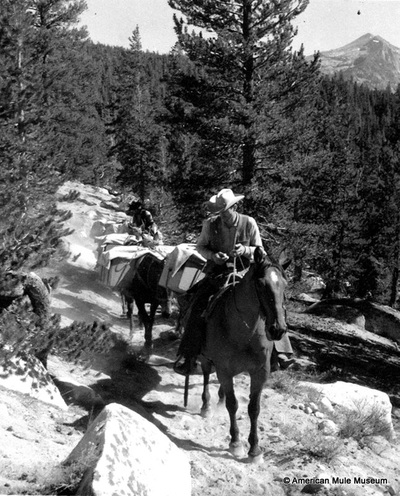

The trail was built and supervised from the east side of the range because the distances to the trail route were shorter than on the west side. The entire length of the trail was constructed to be passable by pack and saddle stock as this was all a roadless wilderness. Trail construction was under the management of Forest Service Ranger, Roy Boothe, who later became Supervisor of the Inyo National Forest, headquartered in Bishop. However, Sequoia and Sierra National Forests did a great amount of the construction work. Commercial pack stations contracted to supply packers and mule strings that transported all the tools, materials, trail crew and supplied the camps during this major construction. Pack mules, saddle horses and large draft teams were vital to the trail construction process. Most of the pack stock used in the Sierra were and still are hardy and sturdy mules.

By 1927, most of the trail had been completed. Before the construction of Forester Pass, the Muir Trail went east over Junction and Shepherd passes. Forester Pass, completed in 1932, is a most spectacular pass and engineering marvel, providing a direct crossing of the high precipitous Kings-Kern Divide. This is the highest pass, at 13, 156 feet along the trail. The descent on the south side entailed much blasting to carve out the trail across sheer granite. Sadly, a young man, working on this section, was killed, the only fatality in the long trail construction process.

The last section, slated for construction, was the “Golden Staircase” (many steep switchbacks) on a cliff below Palisade Lake and nearby Mather Pass. The Mather Pass trail was cut into granite and was the last pass constructed. It was named for Stephen Mather, the first director of the National Park Service and was completed in 1938.

The final construction work during the Great Depression used labor of men in the CCC program. This was some of the most difficult construction work entailing much blasting in granite and these CCC crews built an amazing trail. The crews had to be secured by ropes when working on sheer granite sections.

The Trail begins in Happy Isles, Yosemite Valley and ends at the summit of Mt. Whitney making the total mileage 210.4 miles. However, in order to reach a trailhead road, it is an additional 10.6 miles from the summit of Mt. Whitney to Whitney Portal making the total 221 miles. Most of the Trail lies above 8,000 feet in designated wilderness and it took 46 years to complete construction. The PCT (Pacific Crest Trail) shares the John Muir Trail through its over 200 miles. Good Lateral trails on both the east and west sides of the range make the John Muir Trail accessible the length of the trail. However, the trail is not bisected by any trans-Sierra roads and this is the longest stretch of wilderness in the continental United States. The Forest Service and Park Service still use mule strings to carry in supplies, tools and provisions to maintain and repair this amazing trail.

The U. S. Cavalry monitored Yosemite and Sequoia Parks before the National Park Service was organized, and in so doing, they cleared and improved existing trails. When necessary, army soldiers constructed new trails in order to better access a destination. These trails were all passable by horseback and pack mules. Everyone rode horses or mules and only hiked to reach a locality not accessible by riding animals.

Towns on both sides of the Sierra Nevada financed trails to access destinations and private entrepreneurs built toll trails. Local livery stables provided horses, pack mules and guides.

Theodore S. Solomons, a charter Sierra Club member, conceived the lofty idea for a high trail along the backbone of the Sierra Nevada between Yosemite and Mt. Whitney. He thought the north to south high trail should be as near to the main crest as possible. From 1892 through 1897, Solomons made many extended pack trips of exploration, principally in the upper branches the San Joaquin River system. His concept of the route required that the trail be passable by saddle and pack stock. Solomons was later helped in his explorations by Joseph N. LeConte (Little Joe), a professor of Engineering at UC Berkeley and Bolton Coit Brown, a professor of drawing at Stanford University and his wife, and Walter Starr, Senior. Their writings and detailed maps, contributed greatly to the overall knowledge of the High Sierra. Walter Starr later finished and published, The Starr’s Guide to the John Muir Trail in 1934. His son, Walter Starr, Jr. had written the manuscript for the book before being killed in a fall while climbing in the Minarets. This book is still the manual for travel in the Sierra.

In 1914, John Muir, who was president of the Sierra Club, died unexpectedly. Club members searched for a lasting way to honor him. Meyer Leissner, came up with the idea of naming this same proposed north to south high trail after Muir, calling it the John Muir Trail. The Club formed a committee to work with the State of California to acquire funding for trail construction. The committee consisted of: Meyer Leissner, Chairman, Walter Huber, David Barrows, Vernon Kellogg and Clair Tapaan. The State Engineer, Wilbur McClure, looked at the various trail options and selected a route that was mostly the route laid out by Solomons and LeConte.

The State of California allocated $10,000.00 to begin construction in 1915. McClure negotiated with the newly organized Forest Service to manage and supervise the trail work with the State furnishing the funding. In 1917, the State again voted to appropriate another $10,000.00. There were 3 more additions of construction money from the State – in 1925, 1927, and 1929. Due to the Great Depression, the State of California could not contribute any further funds. The National Park Service (that had been established in 1916), jointly with the Forest Service, funded the remaining trail construction.

The trail was built and supervised from the east side of the range because the distances to the trail route were shorter than on the west side. The entire length of the trail was constructed to be passable by pack and saddle stock as this was all a roadless wilderness. Trail construction was under the management of Forest Service Ranger, Roy Boothe, who later became Supervisor of the Inyo National Forest, headquartered in Bishop. However, Sequoia and Sierra National Forests did a great amount of the construction work. Commercial pack stations contracted to supply packers and mule strings that transported all the tools, materials, trail crew and supplied the camps during this major construction. Pack mules, saddle horses and large draft teams were vital to the trail construction process. Most of the pack stock used in the Sierra were and still are hardy and sturdy mules.

By 1927, most of the trail had been completed. Before the construction of Forester Pass, the Muir Trail went east over Junction and Shepherd passes. Forester Pass, completed in 1932, is a most spectacular pass and engineering marvel, providing a direct crossing of the high precipitous Kings-Kern Divide. This is the highest pass, at 13, 156 feet along the trail. The descent on the south side entailed much blasting to carve out the trail across sheer granite. Sadly, a young man, working on this section, was killed, the only fatality in the long trail construction process.

The last section, slated for construction, was the “Golden Staircase” (many steep switchbacks) on a cliff below Palisade Lake and nearby Mather Pass. The Mather Pass trail was cut into granite and was the last pass constructed. It was named for Stephen Mather, the first director of the National Park Service and was completed in 1938.

The final construction work during the Great Depression used labor of men in the CCC program. This was some of the most difficult construction work entailing much blasting in granite and these CCC crews built an amazing trail. The crews had to be secured by ropes when working on sheer granite sections.

The Trail begins in Happy Isles, Yosemite Valley and ends at the summit of Mt. Whitney making the total mileage 210.4 miles. However, in order to reach a trailhead road, it is an additional 10.6 miles from the summit of Mt. Whitney to Whitney Portal making the total 221 miles. Most of the Trail lies above 8,000 feet in designated wilderness and it took 46 years to complete construction. The PCT (Pacific Crest Trail) shares the John Muir Trail through its over 200 miles. Good Lateral trails on both the east and west sides of the range make the John Muir Trail accessible the length of the trail. However, the trail is not bisected by any trans-Sierra roads and this is the longest stretch of wilderness in the continental United States. The Forest Service and Park Service still use mule strings to carry in supplies, tools and provisions to maintain and repair this amazing trail.