|

Video review by Holly Subia

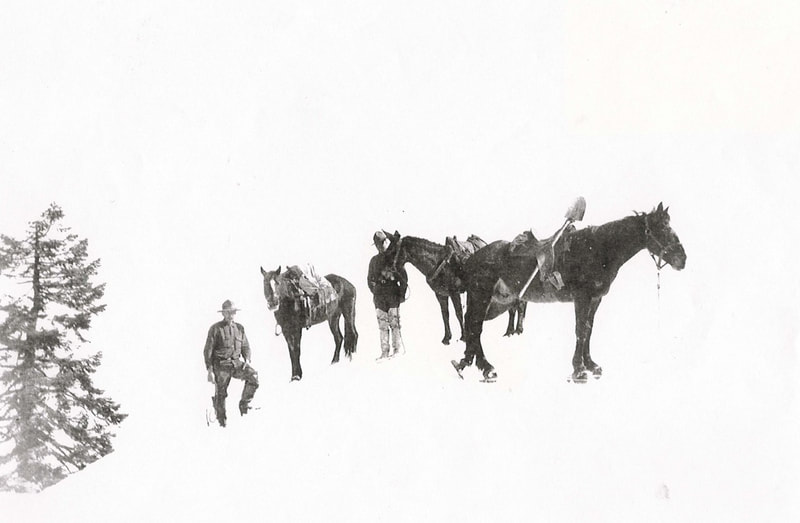

I recently watched a great video about mules on snowshoes. But to say it was just about mules on snowshoes is selling this video short. I also learned that any mule packing I did in the Sierra Nevada was amateur compared to what these men did. This video is called Bill Balfrey’s Mules on Snowshoes and made by Video Mike. You can find it on Mike’s web page under “Documentaries & Historical Subjects”. (https://video-mike.com/collections) The video starts with a presentation by Bill Balfrey where he presents and explains different equipment used by the team that packed mail and mining equipment into the mountains in northwest California. One of the pieces of equipment shone in the video is a snowshoe worn by the mules that helped deliver mail into the mountains during the winter. Each shoe was a square piece of wood and was usually about 10 inches square. There was some size variation with the different styles and who made the snowshoe. The wood of the snowshoes was treated with bees wax and boiled linseed oil to help preserve the wood and prevent the snow from sticking to the snowshoes. There was a slit in the wood where the mule’s toe would sit and two small holes where the mule’s heals sat. These holes were to accommodate the toe and heal caulks on the mule’s shoe. These holes, as well as a special metal clasp that went over the mule’s hoof, held the snowshoe in place. These snowshoes made it possible to take mules into the mountains, to carry mail, during the winter. Bill said they delivered the mail for about 12 to 14 years and only missed 2 days of mail delivery. Bill said they would train the mules to wear the snowshoes by gathering up the mules on a summer day and hold them all in the corrals. Snowshoes would be put on all the mules and the mules that figured out how to walk in the snowshoes worked the winter shifts. The snowshoes were just the first of many obstacles the mules learned to overcome during the winter. Hard packed snow would hold a mule in snowshoes but if the snow got to soft the packers would lay the mule on it’s side, put blinders on the mule and then slide the mule over the soft snow on a sled. Mules walked through deep trenches and tunnels dug into the snow and jumped down snow steps as high as 8 feet. Luckily the winter loads carried by the mules were mostly just U.S. mail. The mules did not carry such easy loads in the summer. During the summer these mules were used to pack all supplies needed at the mines located in the mountains. If one of the mines needed a tractor, the tractor was dismantled and packed in on mules. The tractor was then rebuild at the mine site. Because of the size and nature of these loads, most of them were top loads with little to no side loads. This in and of its self is a feat. These pack strings carried about 600,000 pounds a year. Each mule carried an average of 300 pounds but a mule could be asked to carry up to 600 pounds. A mule asked to carry a super heavy load was retired after they finished that trip. These pack strings worked until about 1920. This is just a short overview of the information in this video. I highly recommend watching this video if you get the chance. To see what these men and mules overcame to get their jobs done is truly humbling.

1 Comment

George L. Garrigues , 1993

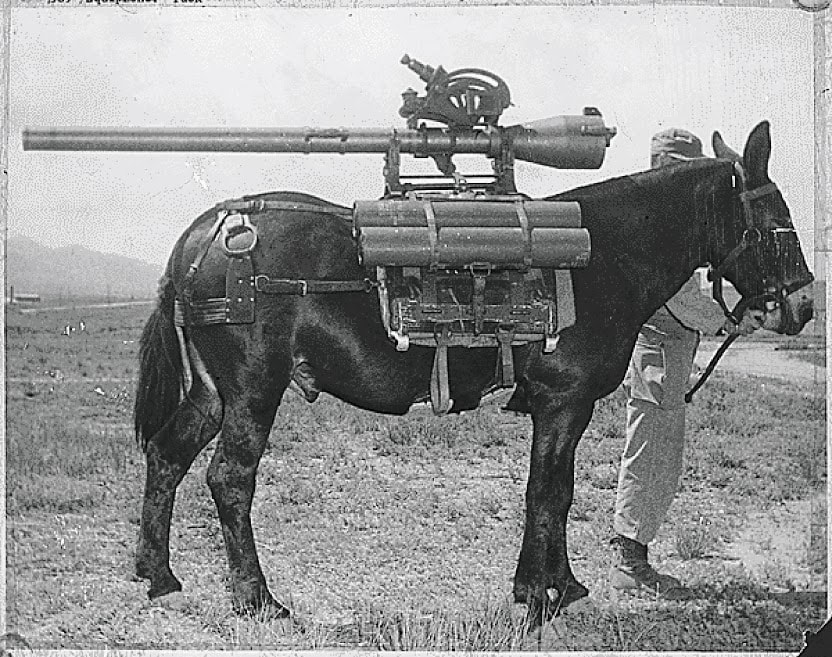

This is a reprint of an article from the 1993 Bishop Mule Days Program There are a lot of mule aficionados and Ervin A. Matthis of Redondo Beach is among them. This the tenth straight Mule Days that he has attended. While not a record by far, it is still impressive. Matthis gained his enthusiasm and respect for mules in Burma during World War II. He was a member of Merrill’s Marauders and the performance of army mules during that campaign proved their worth. He says, “A mule with a full pay load can go anywhere a man can on his own two feet. Mules can even pack their own weight for approximately a mile.” Matthis’ story begins at Fort Lewis in Washington and then goes on to Camp Carson in Colorado —training sites for army mules and the soldiers that taught them. The soldiers worked with the mules transporting normal loads using standard army stock saddles. However, some items required special equipment such as the pack saddle devised to carry the parts of the 1,500 pound 75 mm howitzer. This saddle consisted of a heavy steel frame over a thick leather cover lined with horse hair. It was fitted to the mules so that it transmitted the pressure of the pack to the part of the animals’ back best suited to bear the load. If a mule developed a saddle sore, the horse hair lining could be adjusted to remove the pressure from the sore area. Six mules were required to transport the complete howitzer. (Photos show the different parts ready to hit the trail.) This part of Matthis’ training included some high country terrain in Colorado. The soldiers, mules and their equipment were tested to full capacity. Even at that pace, their climb up and down Pikes Peak was not too big a challenge. Their next episode was a different story. The call for 3,000 volunteers including 100 mule skinners went out across the United States, Panama and the Pacific. It was 1943 and Ranger Unit 5307 Composite (provisional) was being formed for a long range penetration mission behind the Japanese lines in Burma. It soon became known as “Merrill’s Marauders.” From February to May, 1944, the Marauders participated in a drive to recover Burma from the Japanese occupants and clear the way for the completion of the Ledo Road to China. The Marauders were foot soldiers, their equipment transported by mules and a few horses that fought through jungles and over mountain passes in Burma. In five major and 30 minor engagements they defeated veteran Japanese soldiers. They prepared the way for allied advance into China. Matthis was one of the 100 who volunteered from the 98th Pack Artillery. They gathered in India. What followed could be called an ugly type of war. It was more a fight against geography, dank climate, mountainous terrain, matted jungle and disease than against the greater numbers or better weapons of the Japanese. Three hundred men remained in India as a rear echelon—their job to handle supplies and set up air drops for the men on the campaign. The other 2,997 men, 700 mules and horses started the hundred mile march up the Ledo Road to a point where it turned into Burma. Their first mission was to cut the Kamaing Road, a Japanese supply route. After successfully completing this assignment, “Merrill’s Marauders,” continued marching. From one mission to another, meaningless places to us, such sites as Tanja Ga, Shikau Ga, Nhpum Ga and Hsamsinyang, but all vital for the Japanese troops. The mule performance was extraordinary. They proved the benefit of their training. One was a natural leader. When headed up the trail, he followed it. The others fell in line, each behind the mule that he followed previously. Lines to keep them in place or moving ahead were unnecessary. They just moved along the trail doing their job, carrying their loads as expected. After more than 250 miles of jungle travel and combat, the troops had suffered the expected casualties. Mule losses were relatively low, although they were in a run down condition after carrying heavy loads with a minimum of grain rations. Top priority for the re-supply airdrops was ammunition and combat necessities. Men’s rations and grain for the animals were last on the list. The same applied to transport supplies on the mules. When a mule was lost, its load had to be distributed among the remaining animals. What they couldn’t carry was dropped. Grain was the first to go. The men carried their own rations on their backs. The mules were able to survive on bamboo leaves and the ground foliage, but the horses took longer adapting to the change in diet. Matthis comments, “Mules are not about to starve as long as there is something to chew on.” The fighting was fierce and physical exhaustion from seven weeks of marching through the mountains, jungles, mud water with insufficient food plus disease and nervous strain had drained the men and the animals. When they reached Nhpum Gu, one battalion was surrounded by the Japanese. It took almost two weeks to free the encircled men. During this fight, several pack animals were killed. After the battle, orders were received to capture the airfield at Myitkyina about 150 miles away. It was the only all weather air strip in Burma and vital to Japanese operations in that area. It was the beginning of the monsoon season and raining every day. The route followed a native foot trail over the Kumon mountains. It became almost impossible for the men and the heavily loaded mules, both in run down condition, to make it over the pass. Nevertheless, they started up the steep, slippery trail. Several slid off the trail and were lost –six in one slide, twenty in another. It was impossible to get some of the mules back on the trail, most rolled, 100-200 feet down the mountain side and had to be shot. At times the climb was so steep that the soldiers unloaded the mules and carried their loads. Sometimes lines were tied to the top heavy loads, snaked around a tree and, with the men pulling, the mules were able to make it up the trail. The end of the day brought sick call for the mules. The vet treated saddle sores as best he could and the horse hair in the pack saddles was adjusted to reduce the pressure. Regardless of its condition, if a mule could walk, he was loaded and ready to go at daybreak the next morning. Once the task of crossing the mountains was behind them, the men begun a forced march to the airfield. Going steadily for two days and one night, with only ten to fifteen minute breaks, they reached their goal. The mules kept up. After a hard battle, the airfield was captured. General Stilwell flew to it the next day to congratulate the victors. The airfield was more than an objective – it was the last hard core center of the Japanese in Burma. The victory effectively cut off the Japanese supply line into the Hukawng Valley and virtually eliminated the Japanese efforts in that area. This ended the tour of Merrill’s Marauder’s. Of the 2,997 men that began the campaign, 603 survived intact, the 2,394 had been wounded, killed or were disease casualties. This illustrates the difficulties, hardships and dangers that these soldiers and their pack mules encountered. At the termination of this action, the men returned to India and the United States. What happened after that is another story. Matthis’ last comment was, “This was one campaign where the mules proved their worth and played a mighty big part.”  Dear American Mule Museum, This morning I was talking with a friend. Somehow we had a conversation about anvils. So I sent him a picture of mine. I understand this anvil was used in a World War I mule team. A family member received it when the mule team disbanded. That is all I know about it. I was born in 1956 the year the last mule team went out of service. I was looking up some history and was surprised to find your American Mule Museum. I can't imagine anyone else in the world who would appreciate a picture of an anvil. Glad you're there. Be well, Scott Dear American Mule Museum, I have been a fan of the mule for many years now. Now that my beloved Betty the mule is gone, I have a desire to share her wonderful story with you. Enclosed is just part of our story prepared for your consideration and possible inclusion at your museum. If you are interested in more, I would be happy; to write more of her story, send pictures, prepare some video footage of our act on the circus and possibly also send her harness and props to your museum. I look forward to hearing from you, Sincerely, Dave Knoderer The American Mule Museum “The mule is often perceived and misunderstood as being stubborn, but more often than not, is simply smarter than the mule handler.” Betty the Mule Love at first sight Mules helped build America is an understatement. These sure-footed, calm and keen-witted animals were preferred over horses to carry packs up into rugged territory, skid boxes along chaotic shipping wharfs, pull wagons as part of large teams, drag a slip-scoop for an excavator and as riding animals assisting mankind for centuries. The true versatility of the mule was especially obvious when they were trained to entertain in the circus. During the winter of 1987, Dave Knoderer acquired “Betty,” the 12-hand jet-black mule as a baby. Pleased with her pretty head, pleasant disposition and animated trot, Dave began training her to perform at liberty, or completely loose – without restraints – in a circus ring. He also introduced her to the tricks of the ménage; lay-down, sit-up, bow, waltz, etc. for the sake of developing a comedy act. In her he found a willing animal easily enrolled and together they developed their own version of – the animal appears to defy the trainer – a comedy routine. From 1988 until 1990, as the wintertime student of John Herriott; liberty horseman, circus personality and trainer of all kinds of animals in Sarasota, Florida, Dave prepared his animals for circus performing. During those enlightening sessions, Dave rode “Souveran” the American Saddlebred while John rode “American Jubilee” his American Saddlebred. In addition to developing leg extensions, lateral movements and trick poses with their horses, John provided Dave with an understanding of how to start the hind-leg walk with Betty the Mule. During their nine-year career Betty and Dave - Gold-Dust and the Old Cuss - performed across American and Canada, in shrine circus performances, on traveling big top shows, as a rodeo attraction and at special events at nursing homes and educational assembly programs during a time when performing animals were falling from grace. Betty was always willing and attentive in the presence of others and especially kind to the children who adored her. Taking advantage of one last opportunity to perform for fourteen weeks in the summer of 1996, Dave performed two circus acts twice a day; “Souveran” the Haute E’cole or high school dancing Saddlebred horse, and “Betty” the liberty, ménage, trick and comedy mule at the tourist attraction called the Circus Hall of Fame in Peru, Indiana. During her career as “Gold Dust and the Old Cuss” Betty delighted audiences across all of North America. Then she retired as a beloved member of the family. Betty lived to the age of 34. Be Good, Be Well, and Ride Safe Dave "Letterfly" Knoderer |

AuthorAmerican Mule Museum: Telling the story of How the West Was Built – One Mule at a Time Archives

January 2021

Categories |