|

By Marye Roeser

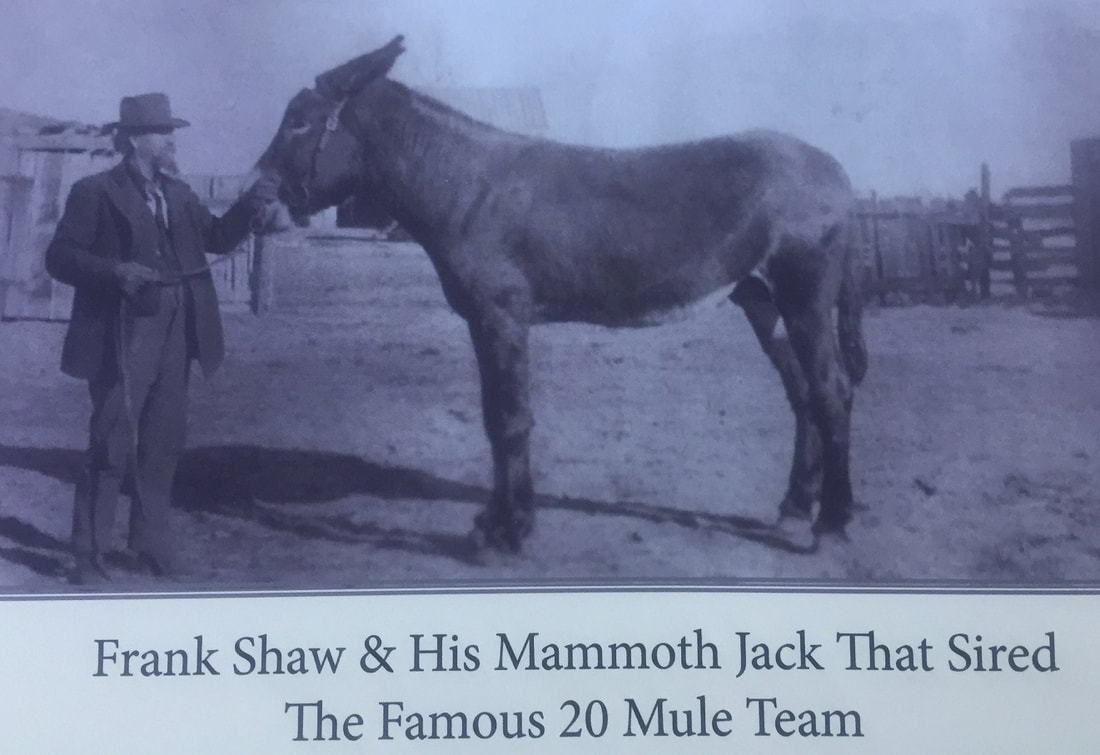

Frank Shaw was a colorful indivedual. He was an early pioneer, rancher, and teamster in Mono County and the Eastern Sierra. In 1865, he owned a cattle ranch in Adobe Valley which lies to the east of Mono Lake. Bodie, California and Aurora, Nevada were adjacent to Adobe Valley and Shaw’s ranch. Frank grew hay on his ranch and pastured his cattle on the meadow lands. He purchased some good draft horses in Columbia, California to start his herd then raised and trained his own draft horses. Frank aquired a Mammoth Jack to breed to some of his mares and produce good large mules. The jack was reportedly mean so he built a high-walled corral to keep him in. Shaw was also in the freighting business as part of his ranching operations. He would haul hay and supplies to Eastern California/Western Nevada mining camps and haul out ore on the return trips. He was considered to be a long line, or long jerk line, teamster. He would use as many as 32 mules on a long line team and even hook up to 3 freight wagons together. The Studebaker Co. built Nevada Wagons for hauling ore and supplies. Frank Shaw likely used some of those wagons as they were popular in this area and local wagon makers built variations of that know style of wagon. F. M. Smith discovered borax at Teel’s Marsh, near Hawthorne, Nevada in 1872. Adobe Valley is just west of Teel’s Marsh and the nearby small mining town of Marietta. Teel’s Marsh was a playa wetland in 1870 often covered with standing water. Columbus Marsh, near Tonopah, Nevada was already in production and not a long distance away. Shaw located borax in his own Adobe Valley and freighted some to Bodie. At that time, most borax was imported from Europe or other areas in the world. Entrepreneurs searched for borax minerals in the United States as they recognized the importance and the demand for local sources. As Smith developed his borax mining works at Teel’s Marsh he needed freighters to move the mineral to markets demanding the product. Bodie was one of those markets and used borax in gold mining. The Teel’s Marsh borax works soon became the largest borax operation in the world. Smith mined the product and contracted the hauling to private freighters. Frank Shaw was soon hauling borax from Teel’s Marsh to Bodie with his long line teams. Rhodes Marsh was 9 miles south of Mina, Nevada near what is now Highway 95. There were maybe 200 acres of salt ponds at Rhodes Marsh. Salt was hauled from Rhodes Marsh to Aurora, Nevada beginning in 1862. Borax was discovered in Rhodes Marsh the 1870s. The area had a simular borax production as Teel’s Marsh. From 1874 to 1881, one ton per day was produced at Rhodes Marsh. Beginning in the late 1860s Frank Shaw hauled hay from his ranch to Rhodes Marsh. As Frank was known to haul ore on his return trips, it is quite likely he hauled borax back to Aurora and later Bodie. In about 1880, Smith moved his operation to Death Valley where he discovered more borax. There Smith set up Harmony Borax Works. The location in Death Valley was very remote and Smith needed to freight the borax produced at the mine to the railroad in Mojave. Smith was having to use his own wagons and teams to make the long haul to the Mojave railroad. Since Smith had previously dealt with Frank Shaw at Teel’s Marsh, Smith contacted Shaw around 1881 or 82. Smith purchased 18 mules and 2 draft horses from Shaw along with two wagons. This is how 2 wagons and a team of 18 mules and 2 horse became one of the first “Death Valley 20 Mule Teams!”

3 Comments

The American Mule Museum (AMM) continues to collaborate with Laws Railroad Museum and the Death Valley Conservancy to build a Death Valley 20 Mule Team exhibit.

The latest update is that the fiberglass mules have been placed in the exhibit. They are harnessed and hitched to the Borax wagons. Work continues at the exhibit site and the next step is to develop interpretive installations to add educational elements to the exhibit. This collaboration is one of the ways the AMM is using funds raised by members to uphold their mission while continuing to work towards a location to house the Mule Museum. Submitted by Jennifer Roeser and written by Wendy Bailey The "Best Show Harvest Spectacular" in Woodland, California, was an absolutely amazing experience. The show was a nostalgic remembrance of the evolution of farming here were Gargantuan steam tractors blowing their lonesome whistles, early combines chugging away, and a host of beautifully and carefully restored antique farm equipment. At the center of the show was the thirty three mule Schandoney hitch driven by George Cabral who is 85 years young and Gene Hilty in his mid 70's. Each a master teamster who has devoted his life to learning the fine art of driving large hitches. The setting at Woodland was delightful, a field of buckskin golden wheat aglow in the sun and ripe for the upcoming harvest. The hitch progressed throughout the week, 33 different mule personalities, and as many handlers would come together to develop a huge hitch, cooperating and working as one. It was amazing to experience mules and harvester working in a peaceful harmonious coexistence; magically transporting one back to a different way of life. The harvester, a 1905 Holt, was an archaic monstrosity and a wonderful thing to behold in its uniqueness. Its own specialized crew worked tirelessly to keep it running, and assured us that like a mule, it had quite a personality of its own. While engaged, the huge harvester made a howling grinding noise that became the soothing sound of wheat production circa 1905. When the harvester had passed, there were bountiful sacks of wheat lying in the field to be picked up by a following wagon. Toward the afternoon, the hot sun beat down relentlessly. The humidity required sheer endurance of man and mule for the determined production and yet never a complaint or disagreement was ever heard. Expert teamsters like Jimmy Glynn never took a break while the mules were hitched. The camaraderie, friendships forged, tall tales, and the day's events retold over a delicious meal and surrounded by restored chuck wagons made it a week to remember. Near the end of the week's activities, George Cabral and Gene Hilty passed on the lines of the mighty 33 mule hitch to the new and younger generation of master teamster Luke Messenger, leaving behind the legacy to be continued. As the organizer of the event, Luke Messenger had led the production with a serene tact and diplomacy which had an amazing effect on mule and man, bringing out the best in both. How he could pull this off with all of the demands of the event placed upon him was beyond me. His whirlwind of non-stop activity and immeasurable energy and hospitality earned the respect and fondness of all. To bring the entire event into perspective and give appreciation of today's conveniences arid amazing farming production, there was a demonstration given by Tony Moules who had grown up in the Azores Islands off the coast of Portugal. As a boy he had harvested and thrashed wheat by hand as they did not have motorized tools on the island until 1976! We witnessed firsthand the laborious and time consuming effort that reaping and thrashing wheat required. Tony caught his breath and explained how they creatively built their own thrashers from tree branches and oxen hair; the only tools and materials available to them. And we thought the 33 mule drawn harvester was a lot of work! Tony finished by reminding us of how extremely privileged we are to live and work in the United States. And what a country we live in where we can relive the past to help us appreciate and build the future. 33 Mule HitchBy Rick Edney

In August of 2010 my friend Luke Messenger called me to talk about a huge responsibility he had accepted, organizing a large mule hitch to pull a restored 1905 combine at the antique farm and harvest show in Woodland, CA. This was done in 2008 with 27 mules but this time there was a challenge to put a 32 mule hitch together. He told me not to plan any early season pack trips for the summer of 2011 because he was already counting on my mules and my help. I couldn’t refuse a chance to work with master teamsters such as George Cabral and Gene Hilty to say the least being a part of recreating history. My son Wes and I traveled to Woodland on Saturday June 25th where we found our camp was already being set up on the edge of the field of wheat that we would be harvesting. We had brought our 5 draft mules and my saddle mule that we intended Wes to ride to help with crowd control. George Cabral arrived later that day with his 4 mules then Cathy Smith with hers. We had a 4 sided picket line with a large stack of oat hay placed in the middle. By mid week we will have 33 mules tied to it. Sunday morning I harnessed my 5 draft mules, leaving my riding mule Buckwheat tied to the picket line. George saw this and asks why I wasn’t harnessing him. I explained that we had tried to break Buckwheat to harness years ago but he was non-compliant to say the least. George, in his soft voice told me to harness him “we’ll see what his problem is”. Gene overheard the conversation and added, “No way were leaving that big boy out of the hitch”. “OK,” I replied, “just remember it was your idea, not mine”. We hitched my 6 abreast on the large training cart then hitched 2 of George’s mules as leaders then we chained my flat bed truck loaded with hay to the back to be used as breaks. Buckwheat kicked, lunged and bucked all the way down the field before settling down; then he just insisted on doing most of the pulling himself. Soon another load of mules arrived so we put another team of six behind mine giving us 14. It didn’t take long before they were all driving well so we decided to hitch them to the Harvester that we intended to use and get them used to the terrible noise it makes when engaged in gear. The anchor truck was also moved to the harvester for safety. Believe it or not but when we put the machine in gear those mules pulled so hard that the pickup was dragged with wheels locked up for quite a ways before they excepted their predicament. That got our hearts pounding. We decided to stack more hay on the truck. All 14 began driving well and we were making progress when the machine broke down, ending our training session for the day. Tuesday morning found us back out on the training cart, while repairs where being made to the combine, but soon lightning was flashing and thunder was getting close so we headed in not wanting to be caught out in the field asking for trouble. It rained one and a half inches that day leaving our camp completely under water. That was also the day that most of our remaining participants arrived. When people pulled off the paved road that is where they had to stay the night. The mud was unbelievable; Luke pulled pickups out with his Draft horses. It was the next afternoon before we could resume training again, using the large cart. A new team of six was hitched in front of mine and things were going smoothly when the six-up evener broke at the pin. The metal evener slammed into the hocks of my mules and they jumped right into the metal eveners of the team in front. Fortunately they all stopped, as mules do, and let us help them without panicking and causing more injury to themselves. I had a bit of doctoring to do but they would all be back to work in the morning. I started personally checking all this old equipment each day before hitching any mules to it as did Luke and Gene. By now our camp had grown fairly large, I’m guessing close to fifty total. We assigned each team of six to one person and he recruited helpers from the 20 some teamsters that showed up to help. The goal was to recreate an old time harvest camp and that’s exactly what we had become, working from sunup to sundown. Every evening there were chores to do, from trimming hoofs to repairing harness. We were constantly repairing harness. Fact is we had a repair shop set up under a large oak tree. Everybody pitched in to help and the camp cooks kept us well fed. After dark a few of us would gather for a cocktail and a story or two then we would hit the bunks exhausted. We had become more than a camp we had become a community. By Thursday we were running out of time but fortunately all the remaining mules were fairly bomb proof except for Norms bay mule, Lucy, who had never been in harness before. Just in case we needed an extra, we decided to give Lucy a crash course on the training cart with 5 other well broke mules. She managed to knock down three men before we even got her hitched and then the real rodeo was on. So far I liked Lucy because she made Buckwheat look like a real gentleman. Down the field we went with Lucy doing her best to break free, she was right on the verge of hurting herself when she just stopped her rebellion and walked out like she belonged there. We traveled a short distance before she again threw another fit this time giving in a little quicker. Gene advised us that she would probably try one more time and sure enough he was right. After that third try of rebellion, she accepted her new job. That was all the time we had to spare on a mule we didn’t intend to use any way. The storm had cost us a day and a half and we only had 26 mules on the harvester. We planned to get an early start Friday morning, adding our last team of 6 right before our first show. It was show time and all 32 mules were in position, the truck was still anchored to the back of the harvester, and out walkers had lead ropes on all the mules on the outside of the hitch. We not only had to worry about our safety but now there were several hundred spectators to worry about. George climbed the Jacobs Ladder, a platform high above the wheel team; from there he would drive the two leaders using 90 foot lines. We had lines to the six wheelers along with the swing team in front of them; I would drive these mules from my position at the base of the ladder using the bottom rung as a seat. From here I could hold them back somewhat and help with the 90 degree turns we planned to make. Luke led the leaders forward stretching the fifth chain tight then George called “Molly” and we were off. The machine makes a terrible whine and the wheelers and swing team about pulled my arms out of their sockets but after a few yards I was able to get them collected. Everything was lining out well but then we had to stop for adjustments. We no sooner got started again and we had to stop because the machine broke. A quick repair and off we went again. Each time we started it got harder for the leaders to start the whole hitch; it was evident that we needed a third mule to help the lead team. A glance at the picket line showed one lonely mule left standing there, Lucy. We moved another broke mule forward and replaced her with Lucy. She made a big commotion for a while but finally resigned to the fact that this was her job to do. Soon we felt we could trust the mules so the truck was unchained from the back of the Combine and soon the out walkers unsnapped their lead ropes and stepped aside. We were now a working 33 mule hitch. One of the show organizers did some research and informed us that this was the first time since 1934 that a 32 mule hitch has been used and we just broke our own record with 33. Saturday morning went much smoother. Gene drove from the top of the Jacobs Ladder while Luke trained Wes to do his job up front. We were once again plagued by equipment problems and made several stops but the Harvester crew worked on the machine all thru lunch break and informed us it was ready to go. After lunch George and Gene stood off to the side, it was time to hand the lines to the next generation. They had preserved this art as long as possible and made a tremendous effort to pass it on. It was up to us to keep it going. Luke climbed the ladder and smiled down at me with a gleam in his eye. “Are you ready for this?” he asked. “I’ve been ready since you called last August,” I replied. A nod to Wes and he led the leaders forward till the fifth chain was tight and straight. “Molly” Luke hollered and we made the smoothest start yet. At the first turn Luke started to swing the leaders right and all the teams fell in, I held my wheelers and swing team straight until the combine reached the end of the stand of grain then let the swing team fallow while holding the wheelers in the turn. A perfect turn and we were lined back out heading across the bottom of the field. We had so much trouble before I kept expecting to have to stop. We reached the end of the field and executed another perfect turn; then another. The sackers riding the harvester were working their butts off keeping up with the grain coming down the chute. Our last turn we pivoted that machine on a dime and headed back to where we started, a full trip around the field without a stop. What a great feeling of success. Sundays show was again hampered by equipment problems and we finally had to shut the machine down all together. At a hundred and six years old you have to expect some break downs. Doesn’t matter, we had our triumph. Hopefully we’ll get another chance to make history in the future. |

AuthorAmerican Mule Museum: Telling the story of How the West Was Built – One Mule at a Time Archives

January 2021

Categories |