|

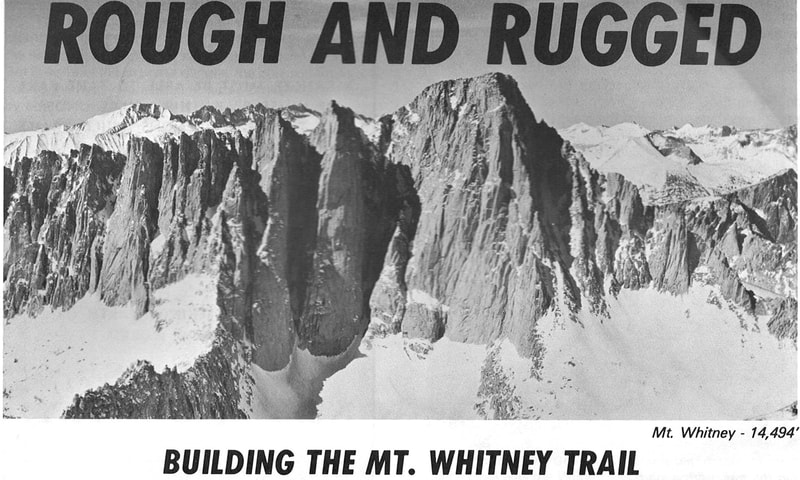

Building the Mt. Whitney Trail

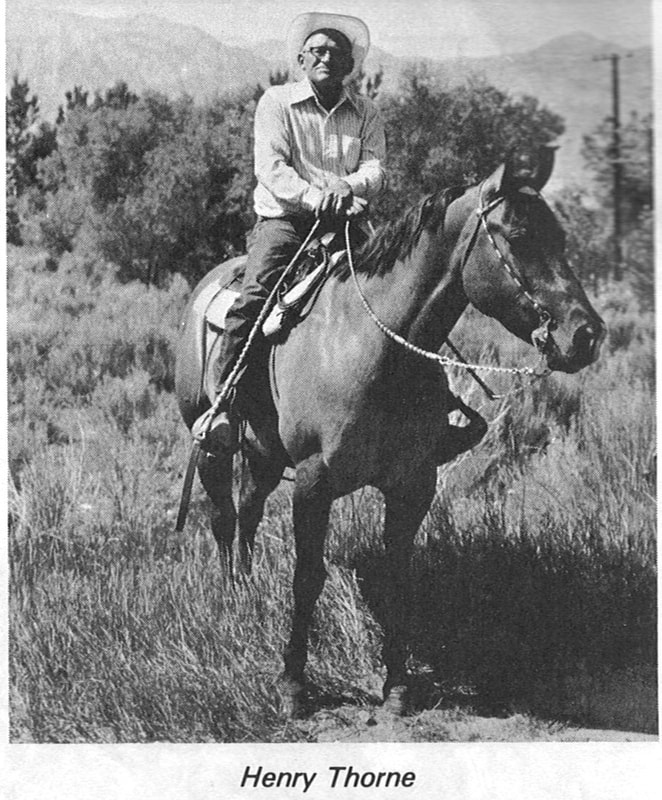

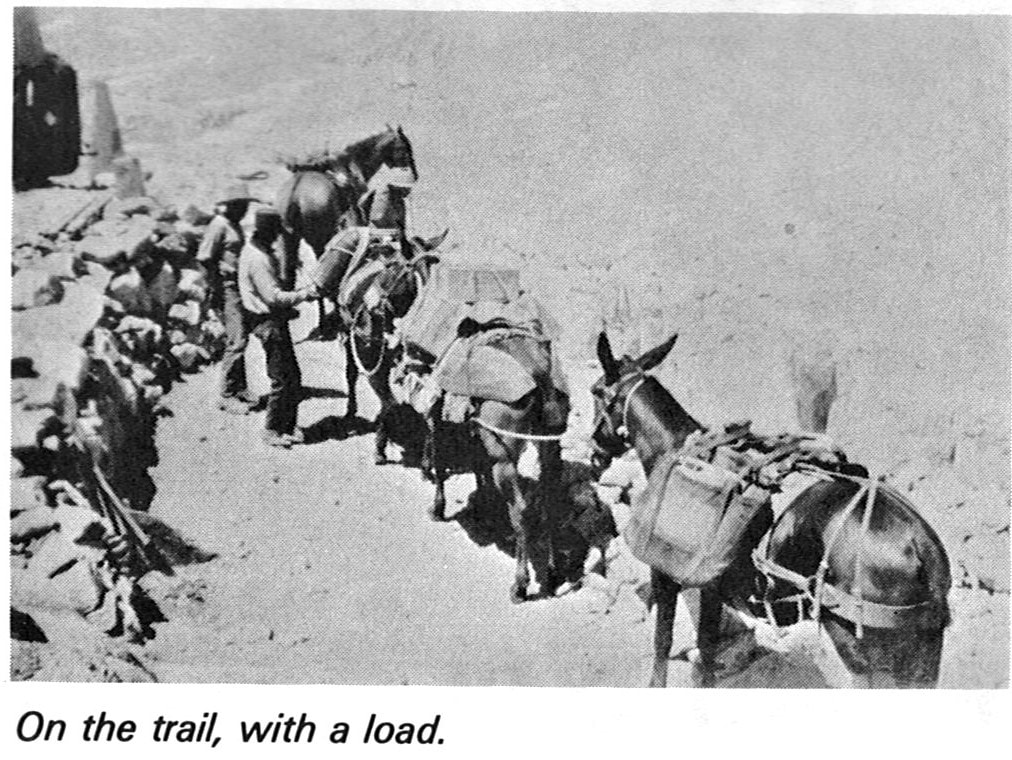

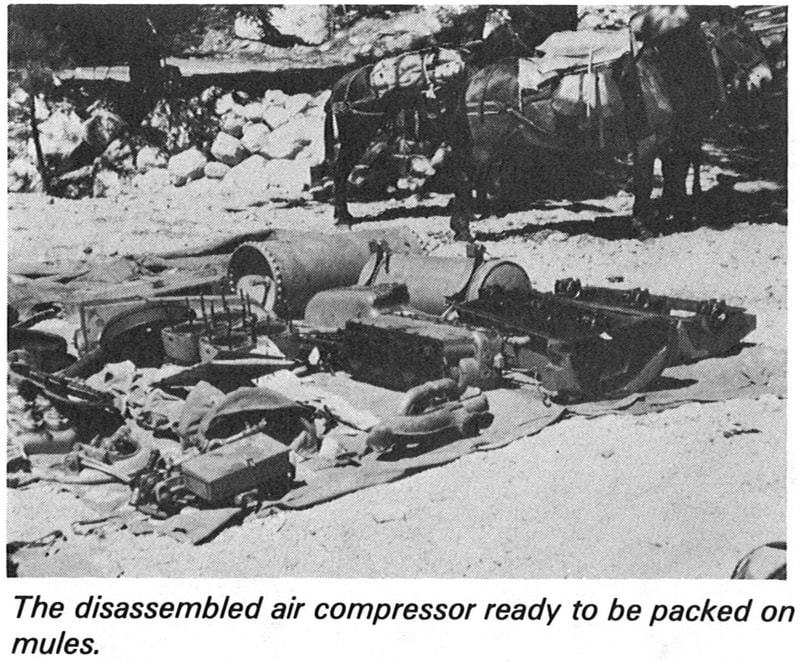

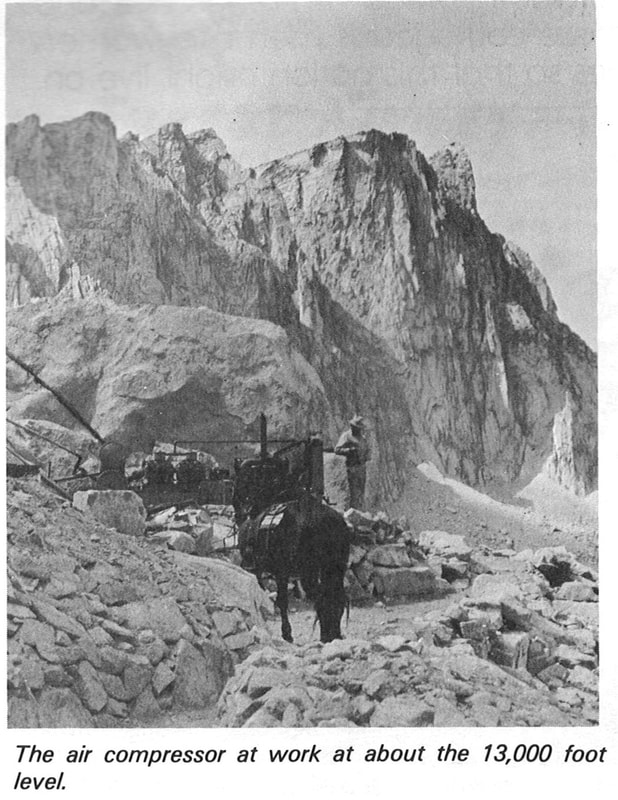

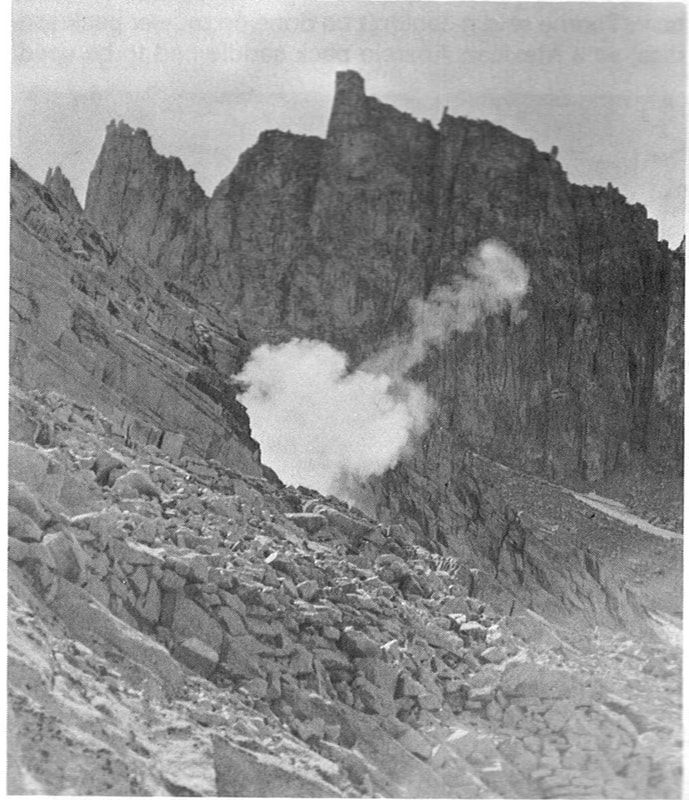

Each year thousands of hikers climb the strenuous trail to the summit of Mt. Whitney, but few realize the vital role the hardy Eastern Sierra packers---and their surefooted mules---played in building the steepest portion of that scenic trail. Henry Thorne, the acting forest engineer in charge of construction for the Forest Service at that time, said the task couldn’t have been done with them. Mules played an integral role in the building of many trails, as well as maintaining more than 700 miles of trail. But Thorne says none of them were as difficult as the portion of the trail from Consultation Lake to Whitney Pass, which includes the well-known 96 switchbacks. In order to avoid deep annual snow drifts, it was necessary to re-route part of the Whitney trail to wind back and forth up the side of a sheer granite wall. This task was begun in July of 1947 when the Mt. Whitney Pack Train at Whitney Portal was contracted by the Inyo Forest to both haul heavy equipment to the 12,000-foot trail camp, and then to keep the hard-working crew supplied throughout the summer season. Drilling cuts as deep as 36 feet into solid rock to make the Whitney trail wide enough was a major job that necessitated the use of an air compressor, which weighed a hefty 10,000 pounds. This Schramm compressor had to disassembled, small pieces carefully packed onto mules for the long journey to the new trail site, and then reassembled. Thorne said the heaviest piece was a crankshaft, which weighed some 344 pounds and was carried on one mule. In addition to packing the heavy air compressor up the mountainside to drill into rocks, some 1,500 feet of pipe had to be packed up the trail. Air was then piped up the mountain to operate the compressor. Packing heavy equipment on mules was no easy task. Thorne said it couldn’t be done on regular pack saddles, so a Mexican Aparejo pack saddle had to be used. Using these saddles required skills and expertise that the early packers had mastered, making them especially valuable in the transport of heavy equipment up the steep slopes. Once the air compressor and piping was packed up the mountain, the mules became a vital link to the outside for supplies of all kinds: groceries to feed the hardworking crews, wood to keep their tents warm on cold nights, dynamite powder to blast through the hard rock, and much more. Thorne recalls that packing the heavy equipment took about four strings of five mules each, and then one string was used to service the camp almost daily. “If it hadn’t been for mules, the whole job couldn’t have been done at all,” said Thorne. “This country never would have made it without them old mules. That’s for sure. “And I don’t think anybody could ever find a better bunch of people to work with than the packers on the Eastern Sierra because they were always cooperative, they always helped,” he added. “They wanted the work done, and they’d go all out to help you.” The packers were also extremely helpful to Thorne who worked for the Forest Service for more than 30 years before retiring in 1963. “I’d worked lots of mules in the Mid-West,” he said. “But they had the load behind them—not on their back. So I had to learn a lot when I came here. The packers were helpful in teaching me. What I know, I owe to them. The 12-man trail crew was a hard-working, hardy bunch who were supervised by Relles Carrasco. Equally important was Carrasco’s wife Lizzie, the famed cook. “They were a great crew to work with,” Thorne recalled. “They never asked about the pay. They asked if Lizzie was cooking. Lizzie was an awful cook.” The job took two seasons to complete, and it was often times a hazardous task. The men, while drilling on the side of a steep bluff, were held by ropes for safety. But in spite of the extreme danger, the only serious injury during the heavy construction was a broken leg suffered by one of men due to a rock slide. In July of 1948 the final phase of the Whitney job was begun and on Sept. 8, the first group to the completed trail was the Wilderness Riders of America accompanied by Forest Service personnel and members of the Mt. Whitney Pack Train. Thirty-five people with their pack and riding stock used the trail this first day. Before completion of the new trail, about 200 people used it over a busy weekend. In recent years a quota system was enacted to protect the environment from overuse, and now 75 people are allowed up the trail each day to climb Mt. Whitney—the highest mountain in the continental United States. Rebecca Cheuvront 1986

3 Comments

by Holly Subia It is no surprise, and well known, that people used mules to haul heavy loads long before they had large tucks. And the “Mac Truck” of mules came from France. The Poitou mule came from two distinct parents. The sire was the Poitou jack, the largest donkey breed in the world. The Poitou donkeys are known for their long dreadlock like coats and their large size. They can get up to 16 hands in height. The dam is a Poitevin mare. Poitevin horses are a large, heavy draft horse used throughout France in agriculture and other draught work. The Poitou mule was sought after the world over, known for it’s strength and gentle nature. The mules were often 17 hands heigh. The demand for these mules was so high a Poitevin mare would usually have one horse foal and then all other foals would be mules. The mules were used in agriculture, freighting and in the military. But after World War II and the industrial age, all three breeds where no longer in such demand and saw a huge reductions in population. The Poitevin region of France once produced around 19,000 mules a year. The annual average of Poitou mules born now is 20 a year. All three breeds, Poitevin horse, donkey and mule are considered endangered breeds. There has been a process but in place to evaluate Poitou donkeys that are not pure bred. If the donkey passed the evaluation it will be included into a breeding program to increase the population of Poitiu donkeys. Today, Poitevin mares will often only have one mule foal in a lifetime. Mares are in a 4 year breeding rotation with stallions. This is to reduce inbreeding and have foals that are not related. These foals will produce the Poiteven foals in the future. The Poitou mule might have to be in decline for a while to assure strong foundation stock for the future. Mules are lucky creatures; they can go extinct but as long as we have horses and donkeys we can make more mules. |

AuthorAmerican Mule Museum: Telling the story of How the West Was Built – One Mule at a Time Archives

January 2021

Categories |