|

By Meredith Hodges

There was a time before the industrial age when one-third of all fifteen million mules on earth were being utilized by the United States. Mules worked in the fields, carried our packs, pulled heavy barges on the canals, plodded through darkness in the mines, guided supply wagons and streetcars about the cities, carried tourists to exotic places like the Grand Canyon and transported army supplies and light artillery for the government. And to help with all the back-breaking labor he faced, man’s invention of the hybrid mule was truly a stroke of creative genius. “No cultural invention has served so many people in so many parts of the world for so many centuries with energy, power and transport as the mule.” During the surge westward, heavy Conestoga wagons laden with all the possessions one could carry were often pulled by teams of mules that were either leased or owned by the early settlers. When cattlemen developed breeds like Texas Longhorns that could endure the harsh climate of the Great Plains, their mules pulled the chuck wagons that followed the large herds as they were driven the long distances to market. Improved farm equipment beckoned farmers to tame the west and what else could manage the vast land and long work hours save the mule? During these times, little thought was given to the possibility that this coveted land was already occupied by numerous Indian tribes. The soldiers were caught in an impossible situation. They were bound by duty to protect and serve the early ranchers, miners, farmers and their families, but were unable to derive any profit from their duty. Indian attacks raged at every turn and mules helped carry the artillery and supplies the army needed to protect its citizens. The armies had been used to fighting in an entirely different climate and, when faced with the gale winds, plunging temperatures and blizzards like they had never seen on the Great Plains, it was often the mule that provided the perseverance and determination to see it through. On rare occasions, the mule served as the only source of food, saving the lives of desperate families and often-hungry Indians. People are generally surprised to learn of the loyal and affectionate nature of the mule. For some reason, they want to believe in a stubborn and vengeful character, but when one reads accounts from individuals, one finds mules to be quite the opposite. In the mid-1800s, the U.S. government, in its infinite wisdom, recognized the value of the mule, yet made foolish provisions for its soldiers in their regard. It was clear that they did not fully understand this animal that resembled the horse but acted nothing like it. In training mules to harness, they often cut traces to the harness so short and hung so low that the mule’s heels would be clipped by the swingle trees when they walked forward. Not wanting to injure itself, the mule would stop when it became sore. This act was acknowledged as laziness. It was only through the good sense of the real mule teamsters that these kinds of errors were corrected. Swingle trees were hung higher between the hock and the heel to allow for a full stride, and traces were subsequently invented with larger chain links at the ends of the drawing-chains to allow for adjustments in length. The American government purchased many mules that were two and three years old—entirely too young for use. If they had purchased mules all over the age of four, it would have saved a lot of heartache and expense. Contractors and inspectors seemed to be more concerned with the numbers they could sell to the government than the quality and usefulness of the animals. When purchased for use, this invariably resulted in the mules being put onto a train with teamsters who knew nothing of their character. Those who know mules know the deep affection they develop for human beings with whom they spend much time. Thousands of young mules were rendered useless by the government’s incompetence and ignorance as to their maintenance and training. Harvey Riley, author of The Mule, published in 1867, recounts, “While on the plains, I have known Kiowa and Comanche Indians to break into our pickets during the night and steal mules that had been pronounced completely broken down by white men. And these mules they have ridden sixty and sixty-five miles of a single night. How these Indians could do this, I never could tell.” Maybe it’s as simple as, “You can catch more flies with honey than you can with vinegar!” Packing was of great importance to government mules, as they were required to carry a wide variety of heavy items over treacherous terrain. In the Northern and Western territories and in Old and New Mexico, nearly all business was done with pack mules and pack donkeys. The Indians adopted the Spanish way of packing, as the Spaniards were noted experts. The Americans developed their own American pack saddle, but it was abandoned soon after its creation. “While employed at the Quartermaster’s depot at Washington, D.C. as superintendent of the General Hospital Stables, we, at one time, received three hundred mules on which the experiment of packing with this saddle had been tried in the Army of the Potomac. It was said this was one of General Butterfield’s experiments. These animals presented no evidence of being packed more than once; but such was the terrible condition of their backs that the whole number required to be placed at once under medical treatment…yet, in spite of all his skill, and with the best of shelter, fifteen of these animals died from mortification of their wounds and injuries of the spine,” Harvey Riley remembers. In 1942, while in the service of the U.S. Army, Art Beaman became familiar with mules in a most curious way. He was working as an Operations Sergeant for a Headquarters in Northern California that determined whether troops were ready for combat. The troops consisted of 204 enlisted men, two veterinarian officers, four horses and 200 mules. Being a non-rider, Art was on and off his horse three times in the first ten minutes of the trip into the mountains. The First Sergeant finally decided to put him on a mule and open his eyes to the redeeming qualities of his mount. The next day, Art was able to say, “That mule and I were really a team…by this time, I trusted my mule so completely that I could have stood up and sang the national anthem as we slipped and skidded along!” The aftermath of this story is really funny. About a week before his pack troop was to be deployed to the South Pacific, some sideways thinker in the Quartermaster Corps sent 200 green-broke replacement mules for his troop. Not wishing to trade the now fully broke mules for the green-broke mules, Art left the 200 mules on the train overnight while he pondered this dilemma. When he returned the next day, he told the men in charge, “There are the old mules and we have the new ones! Evidently, they believed me, or they didn’t care one way or the other, and the green mules were on their way back to Washington!” Those who have experienced the spiritual connection with mules all have their own individual stories to tell. From The Black Mule of Aveluy, by Charles G.D. Roberts, comes one of the most amazing World War I battlefield stories I’ve ever heard. It is the story of a man and a big black mule on a rain-scourged battlefield. “The mule lines of Aveluy were restless and unsteady under the tormented dark. All day long a six-inch high-velocity gun firing at irregular intervals from somewhere on the low ridge beyond the Ancre, had been feeling for them. Those terrible swift shells, which travel so fast on their flat trajectory that their bedlam shriek of warning and the rendering crash of their explosion seem to come in the same breathless instant, had tested the nerves of man and beast sufficiently during the daylight; but now, in the shifting obscurity of a young moon harrowed by driven cloudrack, their effect was yet more daunting.” A second shell screamed down into the lines, scattering deadly splinters of shell ropes, tether-pegs and mules. When it was all said and done, one lone black mule stood back, still tied to the picket line, unable to free himself. With eyes wide in terror, he sought respite from the onslaught, but was unable to find any. Suddenly, a man with tousled, ginger-colored hair appeared at his nose, put his arms around the mule’s neck, as the mule coughed and sputtered, still stunned from the blast. The man quickly untied the black mule and another that was left from the blast and got them to safety. After the attack at Aveluy, the black mule and his new driver were given the job of carrying up shells to the forward batteries. Early that next afternoon, they were plunging deep into rugged territory along a sunken road, muddy from perpetual rain showers, when suddenly the inexplicable happened and there was an array of star-showers that blinded the mule. “When he once more saw daylight, he was recovering his feet just below the rim of an old shell-hole. He gained the top, braced his legs, and shook himself vigorously.” His panniers were still heavily loaded and his driver was not in sight. He soon saw his driver clinging to the far edge of the shell-hole, sinking rapidly in the mud. “He reached down with his big yellow teeth, took hold of the shoulder of Jimmy Wright’s tunic, and held on. He braced himself and, with a loud, involuntary snort, began to pull.” Jimmy Wright remembered the blast and saw where he was. He was afraid his shoulder had been blown off, yet he could move both arms and discovered something was pulling on him. “He reached up his right arm—it was the left shoulder that was being tugged at—and encountered the furry head and ears of his rescuer! Reassured at the sound of his master’s voice, the big mule took his teeth out of Wright’s shoulder and began nuzzling solicitously at his sandy head.” For centuries the mule loyally traversed the course of history with man, though it was never given credit for its valuable contributions. In fact, men perpetrated stories to the opposite and the mule’s legacy became one of laziness, stubbornness and disobedience. Only those humans who were of a character to willingly explore the spirit of the mule were there for its redemption. We are thankful that their stories have withstood the test of time. Throughout history, man believed that he was making progress with each new age, but the blind farmer will tell you, “There’s no such thing as a seeing-eye tractor, and while I am farming with my mule, I can hear the birds sing. I never could with a tractor!” Perhaps we should take note and stop to smell the roses. To learn more about Meredith Hodges and her comprehensive all-breed equine training program, visit LuckyThreeRanch.com or call 1-800-816-7566. Check out her children’s website at JasperTheMule.com. Also, find Meredith on Facebook and Twitter. © 2016 Lucky Three Ranch, Inc. MULE CROSSING All Rights Reserved.

2 Comments

MULES IN THE MILITARY Today’s modern technological advances in the military have provided gadgets and robotics that once seemed straight out of a sci-fi movie. In recent years, the Army experimented with a robotic mule that could carry ammunition and other combat supplies for the soldiers. Since the first version was too noisy for combat, an electric version was created but could not carry more than 40 pounds. [1] A few decades ago, the use of equine was almost abandoned in the military since there was not a definitive need. But the wars in Afghanistan created a necessity for pack mules which are now an integral part of the U.S. Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center in Bridgeport, California. Big Dog robotic mule – Photo courtesy of Wikipedia. In the 1800s, as the West was expanding, mules were a huge resource and commodity for the military – serving as pack animals for the western outposts and pulling wagons to move supplies throughout the West. In the 1850s, military outposts and forts were established in the unsettled West in key locations to provide protection for commerce and emigration. Fort Riley in Kansas is one of the forts that was established in the 1850s to help protect American interests. After the conclusion of the Civil War, Fort Riley aided in the protection of the railroad lines that crossed Kansas. In the following decades, Fort Riley became an important fixture while hosting various regiments of the infantry and cavalry and in 1887 became the site of the U.S. Cavalry School. Fort Riley had a strong equine program that taught cavalry tactics to new mounted recruits. Part of their training also involved using pack mules for various tasks. In the 1940s, Fort Riley trained with mules and Jeeps for different tasks in wartime. Contrary to popular belief, a Jeep cannot travel everywhere in difficult terrain. The mules were referred to as the four-legged Jeep. During the Civil War, mules were crucial in the war efforts – they pulled supply wagons, artillery equipment, and ambulances. At the onset of the Civil War, it was estimated that there were more than a million mules in the country – with most of them residing in the South. Mules were also used as pack animals to transport regimental gear, ammunition, and rations. Additionally they pulled the C & O Canal Boats (Chesapeake and Ohio Canal) which hauled cargo and coal. Some said the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal was the dividing line between the Union and the Confederates, making the mules a target for confiscation by troops from the other side. Mules were also a valuable asset in WWI, WWII, and the Korean War. Again they provided the power to move supplies and ammunition while also serving as pack animals. At the outbreak of the Great War, the British army did not have any mules. According to the 1922 British War Office, England purchased 275,097 mules from America.[1] Mules were transported overseas in specially-designed freighters that were modified with special stalls that could accommodate up to 500 mules. In WWII, mules were commonly transported in C-47s and C-46s to reach war zones, loading six to eight mules on each load in rope stalls.[2] During both wars, the mules were subjected to poisonous gases so that special protection was provided for them. The Hague Convention of 1907 prohibited the use of poison gases and weapons but more than 124,000 tons of gas were dispersed by the end of WWI. The poison gas took a terrible toll on mules, donkeys, horses, dogs, and pigeons. Donkeys have also been used extensively in wartime Besides wartime activities, the military also used mules for delivering aid. In 1906, the US Army was tasked with getting supplies to San Francisco after the devastating fire and earthquake. Congress appropriated $2.5 million in emergency aid. The Army played a major role in relief and refugee efforts and used mule trains to move the supplies to the city. Mule trains delivered aid and supplies to an estimated 300,000 people in San Francisco who had lost their housing after the devastating earthquake and fires in 1906. Photo Courtesy of Library of Congress, George Kleine Collection.

Mules were used extensively in the military in the 1800s. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress, Circa 1909. This photo is from WWI, rights to publish this picture was purchased from Alamy.

The American Mule Museum loves to hear from the fans and supporters. Here is a great letter that we wanted to share with all the readers.

Dear American Mule Museum Personnel, My name is Ryan Damboise and I am from Bristol, Connecticut. I am very thankful to have found the American Mule Museum website because it is providing the benchmark from which my orientation to the American mule is reliably proceeding. My goal is to work as a packer, and much of what I have learned about packmules is the result of your work on the AMM website. I want you to know this because I am preparing for my journey into the mule’s domain, and I am relying heavily on your work to successfully navigate this learning process. It is important to me that I inform you of your role in my self-directed learning, especially because you are helping determine the quality of my preparation as I continue toward my stated goal. I value and appreciate the significant effort involved in your research and writing, as well as the ongoing investment you are making to advance the public’s understanding of the American mule. My progress has been made possible, in large part, due to your concerted effort on behalf of the American mule. I have begun structuring my knowledge base of mule information by reading all of Ms. Marye Roeser’s Mule Tales articles. I have savored each for its artistic flavor and richly informative gleanings. I have also read the blog, the newsletter archive, and have explored many of the websites under the links tab. In fact, I purchased a copy of Ms. Merideth Hodges’ Training Mules and Donkeys because of the link you provided to the Lucky Three Ranch website. I also purchased a copy of Dr. Robert Miller’s Understanding Horse Behavior — The Secrets of the Horse's Mind because I saw a reference to him on Ms. Hodges’ website and was reminded of having seen his name on the schedule of the Bishop Mule Days Celebration's 50th Anniversary proceedings (which is also linked to on your website). I am directing all of my resources, meager though they are, to building a properly set foundation that my future packing team-members can be confident in. I have my Bachelor of Animal Science with several years' experience working as a horse wrangler and trail guide (though not currently), however, I don’t yet have experience shoeing. I have begun to remedy this because I know I need to be a skilled horseshoer in order to be a responsible packer. To familiarize myself with the foremost advances in horseshoeing, I have recently participated in the 17th Annual International Hoof Care Summit. The consensus from related conversations was that I ought to attend a horseshoeing school. My hope is to develop horseshoeing (mules hoeing) proficiency at a program immersed in the mule packing tradition. Would I be correct in thinking the Sierra Horseshoeing School is one such program? Does it continue to operate in Bishop? If it does, would you be so kind as to provide me with the name and contact information of the person with whom I should establish contact? It would be great because I could give a hand at AMM too. Thank you very much for your generous insight. With best personal regards, Ryan Ryan, thank you for letting us know that you have found our work helpful and inspiring. We love getting letters to hear how the AMM has touched lives and inspired people to work with, learn about, and teach others about mules. Please feel free to contact us further if we can help you along your path working with mules. FISH PLANTING PRIOR TO AERIAL STOCKING OF HIGH SIERRA LAKES

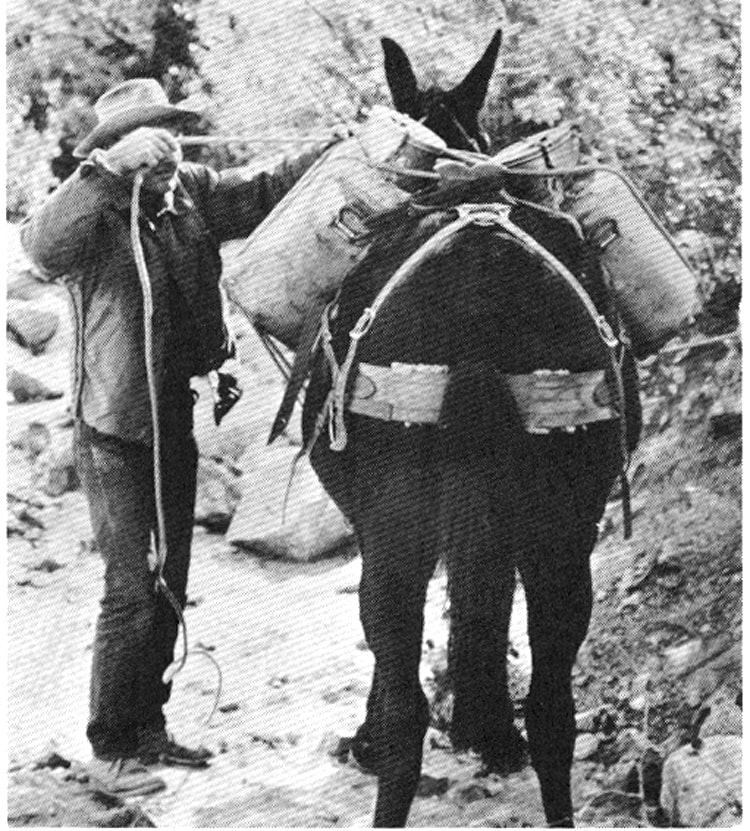

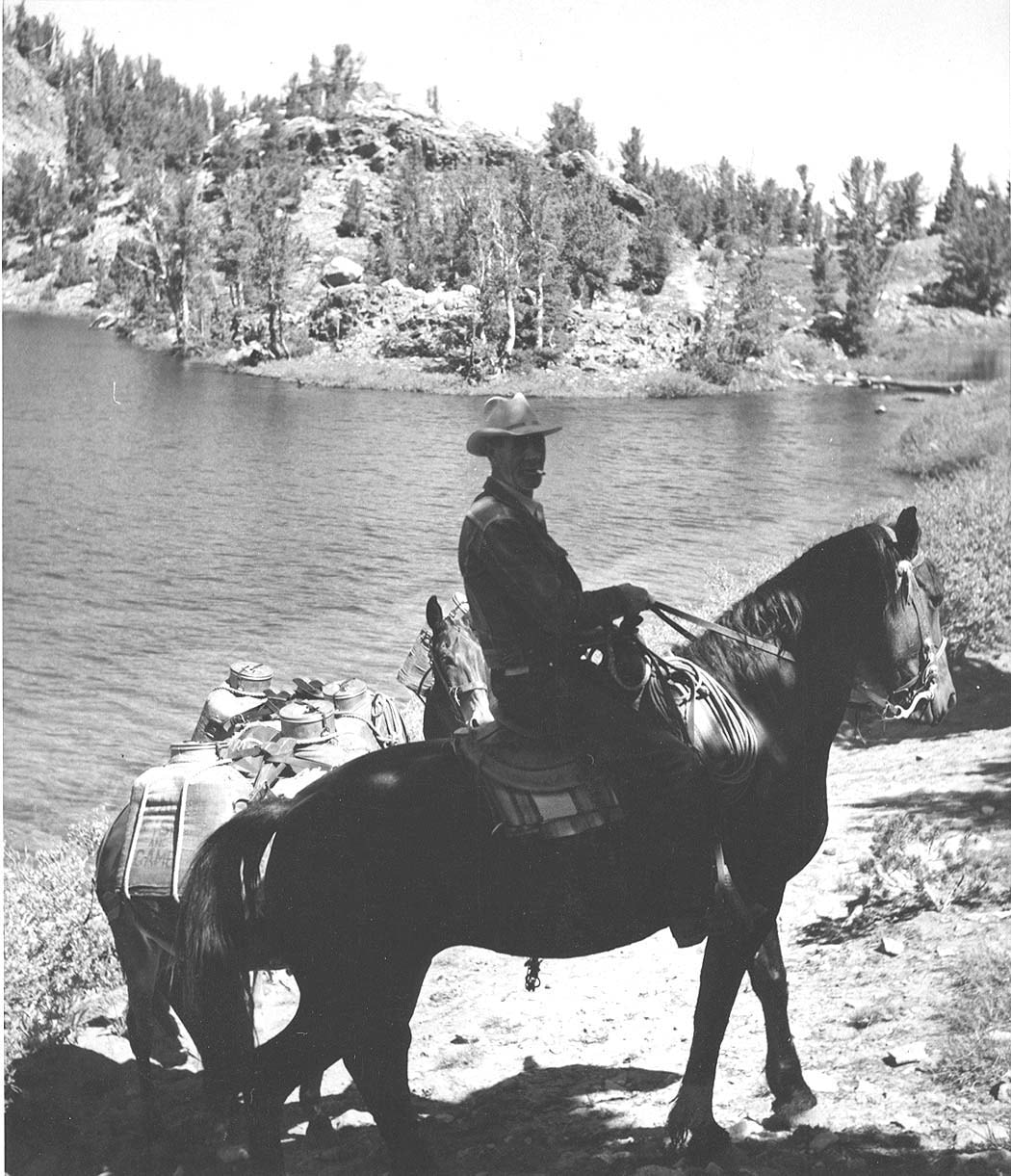

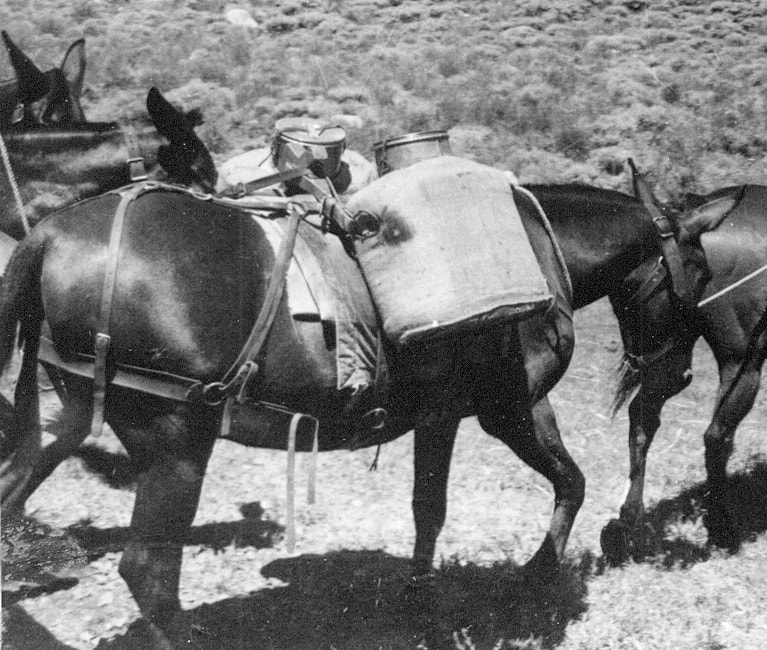

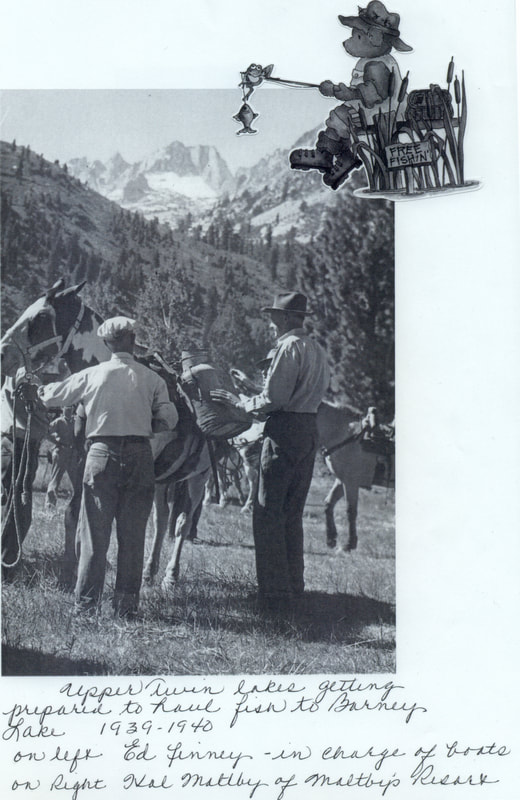

Written by Marye Roeser After World War II ended in 1946, California Department of Fish and Game began aerial fish planting using Army planes and pilots to plant hatchery raised fingerling trout in the lakes and streams of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Much of the Sierra is road less wilderness and is not accessible by vehicle. Prior to aerial drops, fingerling trout were planted in these lakes with strings of mules carrying special fish cans and then on the backs of packers and crew to their destination. These early aerial drops were still not able to plant all lakes due to the restrictions of the early airplanes of that time. Fish hatcheries scattered around the Sierra collected trout eggs and raised trout until they could be planted in the area lakes and streams. Rainbow Trout were the most commonly planted and golden trout were planted in high lakes where suitable habitat was found. Special aerated tanker trucks hauled the “catch-able" fish to the appropriate lakes and streams that they could access. Since the majority of the Sierra lakes and streams are located away from roads; commercial pack stations provided mule transportation for these tiny fish. Their destination; new watery homes in the vast Sierra Nevada range. Fish and Game trucks would haul fingerlings to pack stations where they would transfer the fingerlings to fish cans. These fish cans would then travel by mule back to the high lakes and creeks. These specially designed and constructed cans hold the little fish in water while traveling until they could be poured into the destination lakes and streams. A mule can carry one can on each side hooked onto the packsaddle and lashed in place. In 1952, Lou Roeser remembers helping in the yard at Mammoth Lakes Pack Outfit with a fish planting trip to plant small trout fingerlings. These fingerlings were raised in the Hot Creek Fish Hatchery and trucked to the pack station in a fish planting truck. Stout, gentle pack mules were saddled and cinched ready for the fish cans to be loaded with tiny, young fish. As soon as the cans were packed on a mule that mule would be kept moving by the mounted packer as additional packed mules were tied into the mule string. Trout need adequate oxygen in the cold water and this constant movement kept the water in the cans aerated so the little fish could obtain their necessary oxygen. The mule packer would then move out on the trail leading to the lakes. Employees from California Fish and Game accompanied the packer and mule string to organized the pouring out of the fish at the chosen site(s). The mules were brought as close as possible to the fingerlings planned destination. When the mule strings could not be brought to the waters edge the men than backpacked the fish cans the rest of the way. That same year, Russ Johnson, the owner of McGee Creek Pack Station and Cliff Brunk with California Dept. of Fish and Game, packed golden trout up to Baldwin Lake and a creek above Horsetail Falls. They led the mules as far as feasible. They then hiked, carrying the cans on their backs the remainder of the way. Today, California Department of Fish and Wildlife conducts aerial fish planting with more modern aircraft and schedules air drops every 3 years for each lake. Lakes with more fishing pressure are planted more often. The “Packer with the Mule String” planting method was used throughout the Sierra Nevada range to stock backcountry lakes for many years and still today in some more inaccessible basins. The Sierra have become famous for the great fishing opportunities to be found in many of the lakes, river and creeks throughout the mountain range. Mules, a Family Business

100 years and still going strong. Submitted by Jennifer Roeser Written by Michaela Reese The Reese name has been one in the same with hard work, family values, and good business for nearly one hundred years. The Reese Brothers have taken pride in their family business and have created a way of life for generations to follow and flourish. The journey began in the nineteen twenties with Rufus Reese Sr. starting the family’s long and deep traditions within the mule trading business that has carried on for four generations. Dickie and Rufus Reese are the third generation to continue their family business and stretch it from mules being used to pack, as outfitters, traverse the Grand Cannon, and used in the military. The mules arrive at Greenwood Farms and are taken into the family’s massive gray barn to be clipped, saddled or harnessed, and prepped for their jobs and lives ahead. Some mules are bought for show, others for their brute strength and aid many of the Amish communities in and around Middle Tennessee. From the crop in rural fields Pennsylvania to the French Quarter of New Orleans, Louisiana the Reese mules are used and depended on everyday. Nation wide the Reese Brother’s Mule Company can be seen providing park services in the Midwest, giving carriage rides in California, and quail hunts in South Georgia. Many other business families buy mules from Greenwood Farms and in turn sell them to others in places around the U.S. They sell to individuals or to other businesses. These animals have many functions that Dickie and Rufus capitalized on to ensure the well being of their future family members. The thought of Rufus Sr. in Nashville, Tennessee auctioning and bargaining for his great grandchildren’s future is enough to make anyone proud to know, or be part of, this family. When the brothers took over the family business it was due to a horrific accident resulting in the loss of their father in 1979. The brothers picked up the business with a skill and finesse that not many could achieve. Dickie took over the accounting side having graduated from The University of Tennessee with an Animal Science degree. Rufus, with his no-nonsense attitude, took over the trading of the mules and auctioning. The brothers were, and are, the power-houses of the mule trading world and work exceptionally well together. Dickie states, “We never really fought. Rufus is absolutely the perfect partner.” They worked hard everyday together, learning from one another and gaining the respect of men and women worldwide. Rufus humbly states, “We don’t consider ourselves mule trainers, we keep our operation simple and sell what we buy. The less we have to handle a mule the more profit there is in him.” The ability of the two brothers to save and keep their family business has resulted in the newest generation joining the business. Richard Reese is Rufus’s son. Rufus has taught, and still teaches, his son the way of life on the Greenwood Farm on which Richard grew up. Throughout the years the farm has never really changed just increased in size and ability to profit. The farm makes its name in cattle, mules, and of course mule auctions. The Reese Brothers are famous for their mule consignments in the three big sales. They occur in January, February, and November in Westmoreland, Tennessee. The preparation and work it takes to orchestrate such a sale is awe inspiring and only possible due to the way Richard, Dickie, and Rufus work together. Dickie and Rufus retired, for the most part, in 2018 and have granted the farm to Richard to continue, for many years to come. Richard’s natural skill continues to impress, and provide for, the farmers and business men that depend on the Reese Brother’s Mule Company. Richard has two teachers that know the very inner workings of not only the mules they care for but also the ideals they stand for. Rufus’s daughter Rilla Reese Hanks has also taken after her family name and started up a business for herself and her family. She graduated from The University of Tennessee at Knoxville with a Masters in Animal Science, just like her uncle. She then went on to graduate with her Doctorate of Veterinary Medicine in 2013. Just like Richard; she grew up on Greenwood Farms and has amassed a huge knowledge from working with horses and mules her entire life. Rilla and her husband Drew started their own breeding of mules in 2016 and she is consulted frequently on health issues as a Veterinarian. Dickie still works the three big mule auctions and Rufus can be seen in the barns working with and ensuring the mules are taken care of. Even though the Brothers are retired their relentless passion for their farm, animals, and family is awe inspiring. One hundred years of business is no small accomplishment especially considering the advancement of technology. Throughout all of life’s struggles Dickie and Rufus Reese have been a shining beacon of hard work, family values, and good family business. These men have worked incredibly hard creating a way of life in Middle Tennessee that will live on in the hearts and minds of many Reese generations to come. Don’t miss the famous Tennessee Sales that take place the second Saturday of January, February, March, October, and November. There is a specialty sale the second Friday of January known at the Colt Sale and a sale during the Great Mule and Donkey Celebration at Shelbyville in July each Year. Check out the website at: www.reesemules.com. By Marye Roeser

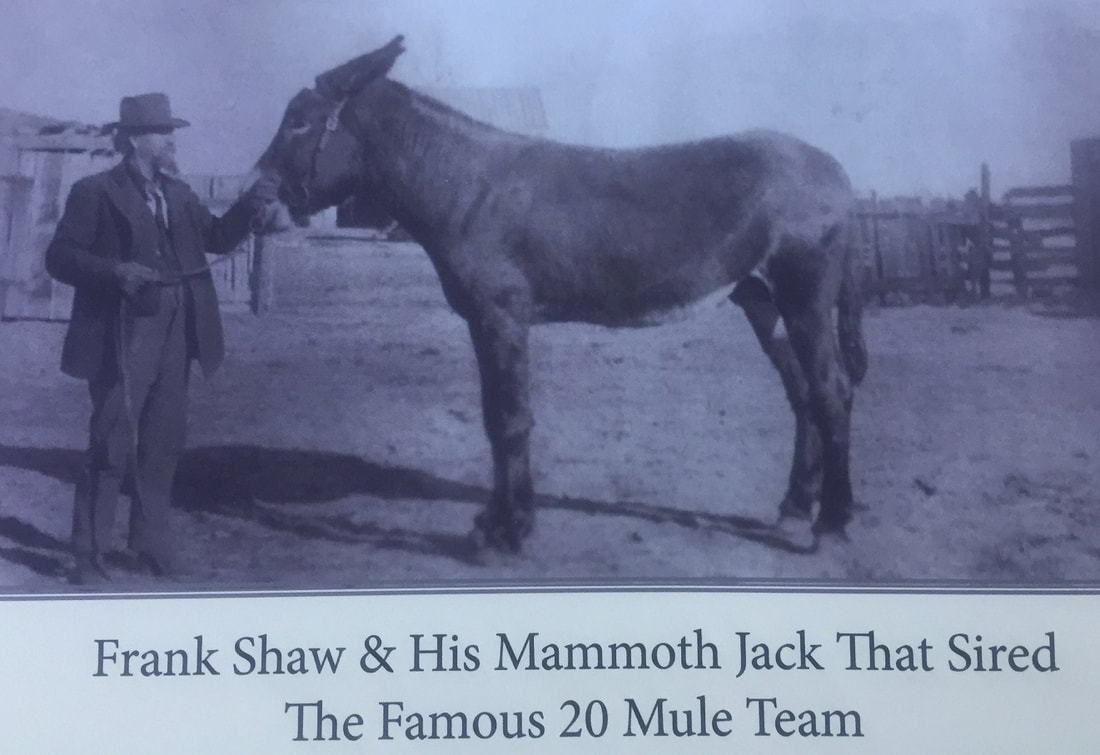

Frank Shaw was a colorful indivedual. He was an early pioneer, rancher, and teamster in Mono County and the Eastern Sierra. In 1865, he owned a cattle ranch in Adobe Valley which lies to the east of Mono Lake. Bodie, California and Aurora, Nevada were adjacent to Adobe Valley and Shaw’s ranch. Frank grew hay on his ranch and pastured his cattle on the meadow lands. He purchased some good draft horses in Columbia, California to start his herd then raised and trained his own draft horses. Frank aquired a Mammoth Jack to breed to some of his mares and produce good large mules. The jack was reportedly mean so he built a high-walled corral to keep him in. Shaw was also in the freighting business as part of his ranching operations. He would haul hay and supplies to Eastern California/Western Nevada mining camps and haul out ore on the return trips. He was considered to be a long line, or long jerk line, teamster. He would use as many as 32 mules on a long line team and even hook up to 3 freight wagons together. The Studebaker Co. built Nevada Wagons for hauling ore and supplies. Frank Shaw likely used some of those wagons as they were popular in this area and local wagon makers built variations of that know style of wagon. F. M. Smith discovered borax at Teel’s Marsh, near Hawthorne, Nevada in 1872. Adobe Valley is just west of Teel’s Marsh and the nearby small mining town of Marietta. Teel’s Marsh was a playa wetland in 1870 often covered with standing water. Columbus Marsh, near Tonopah, Nevada was already in production and not a long distance away. Shaw located borax in his own Adobe Valley and freighted some to Bodie. At that time, most borax was imported from Europe or other areas in the world. Entrepreneurs searched for borax minerals in the United States as they recognized the importance and the demand for local sources. As Smith developed his borax mining works at Teel’s Marsh he needed freighters to move the mineral to markets demanding the product. Bodie was one of those markets and used borax in gold mining. The Teel’s Marsh borax works soon became the largest borax operation in the world. Smith mined the product and contracted the hauling to private freighters. Frank Shaw was soon hauling borax from Teel’s Marsh to Bodie with his long line teams. Rhodes Marsh was 9 miles south of Mina, Nevada near what is now Highway 95. There were maybe 200 acres of salt ponds at Rhodes Marsh. Salt was hauled from Rhodes Marsh to Aurora, Nevada beginning in 1862. Borax was discovered in Rhodes Marsh the 1870s. The area had a simular borax production as Teel’s Marsh. From 1874 to 1881, one ton per day was produced at Rhodes Marsh. Beginning in the late 1860s Frank Shaw hauled hay from his ranch to Rhodes Marsh. As Frank was known to haul ore on his return trips, it is quite likely he hauled borax back to Aurora and later Bodie. In about 1880, Smith moved his operation to Death Valley where he discovered more borax. There Smith set up Harmony Borax Works. The location in Death Valley was very remote and Smith needed to freight the borax produced at the mine to the railroad in Mojave. Smith was having to use his own wagons and teams to make the long haul to the Mojave railroad. Since Smith had previously dealt with Frank Shaw at Teel’s Marsh, Smith contacted Shaw around 1881 or 82. Smith purchased 18 mules and 2 draft horses from Shaw along with two wagons. This is how 2 wagons and a team of 18 mules and 2 horse became one of the first “Death Valley 20 Mule Teams!” The American Mule Museum (AMM) continues to collaborate with Laws Railroad Museum and the Death Valley Conservancy to build a Death Valley 20 Mule Team exhibit.

The latest update is that the fiberglass mules have been placed in the exhibit. They are harnessed and hitched to the Borax wagons. Work continues at the exhibit site and the next step is to develop interpretive installations to add educational elements to the exhibit. This collaboration is one of the ways the AMM is using funds raised by members to uphold their mission while continuing to work towards a location to house the Mule Museum. Submitted by Jennifer Roeser and written by Wendy Bailey The "Best Show Harvest Spectacular" in Woodland, California, was an absolutely amazing experience. The show was a nostalgic remembrance of the evolution of farming here were Gargantuan steam tractors blowing their lonesome whistles, early combines chugging away, and a host of beautifully and carefully restored antique farm equipment. At the center of the show was the thirty three mule Schandoney hitch driven by George Cabral who is 85 years young and Gene Hilty in his mid 70's. Each a master teamster who has devoted his life to learning the fine art of driving large hitches. The setting at Woodland was delightful, a field of buckskin golden wheat aglow in the sun and ripe for the upcoming harvest. The hitch progressed throughout the week, 33 different mule personalities, and as many handlers would come together to develop a huge hitch, cooperating and working as one. It was amazing to experience mules and harvester working in a peaceful harmonious coexistence; magically transporting one back to a different way of life. The harvester, a 1905 Holt, was an archaic monstrosity and a wonderful thing to behold in its uniqueness. Its own specialized crew worked tirelessly to keep it running, and assured us that like a mule, it had quite a personality of its own. While engaged, the huge harvester made a howling grinding noise that became the soothing sound of wheat production circa 1905. When the harvester had passed, there were bountiful sacks of wheat lying in the field to be picked up by a following wagon. Toward the afternoon, the hot sun beat down relentlessly. The humidity required sheer endurance of man and mule for the determined production and yet never a complaint or disagreement was ever heard. Expert teamsters like Jimmy Glynn never took a break while the mules were hitched. The camaraderie, friendships forged, tall tales, and the day's events retold over a delicious meal and surrounded by restored chuck wagons made it a week to remember. Near the end of the week's activities, George Cabral and Gene Hilty passed on the lines of the mighty 33 mule hitch to the new and younger generation of master teamster Luke Messenger, leaving behind the legacy to be continued. As the organizer of the event, Luke Messenger had led the production with a serene tact and diplomacy which had an amazing effect on mule and man, bringing out the best in both. How he could pull this off with all of the demands of the event placed upon him was beyond me. His whirlwind of non-stop activity and immeasurable energy and hospitality earned the respect and fondness of all. To bring the entire event into perspective and give appreciation of today's conveniences arid amazing farming production, there was a demonstration given by Tony Moules who had grown up in the Azores Islands off the coast of Portugal. As a boy he had harvested and thrashed wheat by hand as they did not have motorized tools on the island until 1976! We witnessed firsthand the laborious and time consuming effort that reaping and thrashing wheat required. Tony caught his breath and explained how they creatively built their own thrashers from tree branches and oxen hair; the only tools and materials available to them. And we thought the 33 mule drawn harvester was a lot of work! Tony finished by reminding us of how extremely privileged we are to live and work in the United States. And what a country we live in where we can relive the past to help us appreciate and build the future. 33 Mule HitchBy Rick Edney

In August of 2010 my friend Luke Messenger called me to talk about a huge responsibility he had accepted, organizing a large mule hitch to pull a restored 1905 combine at the antique farm and harvest show in Woodland, CA. This was done in 2008 with 27 mules but this time there was a challenge to put a 32 mule hitch together. He told me not to plan any early season pack trips for the summer of 2011 because he was already counting on my mules and my help. I couldn’t refuse a chance to work with master teamsters such as George Cabral and Gene Hilty to say the least being a part of recreating history. My son Wes and I traveled to Woodland on Saturday June 25th where we found our camp was already being set up on the edge of the field of wheat that we would be harvesting. We had brought our 5 draft mules and my saddle mule that we intended Wes to ride to help with crowd control. George Cabral arrived later that day with his 4 mules then Cathy Smith with hers. We had a 4 sided picket line with a large stack of oat hay placed in the middle. By mid week we will have 33 mules tied to it. Sunday morning I harnessed my 5 draft mules, leaving my riding mule Buckwheat tied to the picket line. George saw this and asks why I wasn’t harnessing him. I explained that we had tried to break Buckwheat to harness years ago but he was non-compliant to say the least. George, in his soft voice told me to harness him “we’ll see what his problem is”. Gene overheard the conversation and added, “No way were leaving that big boy out of the hitch”. “OK,” I replied, “just remember it was your idea, not mine”. We hitched my 6 abreast on the large training cart then hitched 2 of George’s mules as leaders then we chained my flat bed truck loaded with hay to the back to be used as breaks. Buckwheat kicked, lunged and bucked all the way down the field before settling down; then he just insisted on doing most of the pulling himself. Soon another load of mules arrived so we put another team of six behind mine giving us 14. It didn’t take long before they were all driving well so we decided to hitch them to the Harvester that we intended to use and get them used to the terrible noise it makes when engaged in gear. The anchor truck was also moved to the harvester for safety. Believe it or not but when we put the machine in gear those mules pulled so hard that the pickup was dragged with wheels locked up for quite a ways before they excepted their predicament. That got our hearts pounding. We decided to stack more hay on the truck. All 14 began driving well and we were making progress when the machine broke down, ending our training session for the day. Tuesday morning found us back out on the training cart, while repairs where being made to the combine, but soon lightning was flashing and thunder was getting close so we headed in not wanting to be caught out in the field asking for trouble. It rained one and a half inches that day leaving our camp completely under water. That was also the day that most of our remaining participants arrived. When people pulled off the paved road that is where they had to stay the night. The mud was unbelievable; Luke pulled pickups out with his Draft horses. It was the next afternoon before we could resume training again, using the large cart. A new team of six was hitched in front of mine and things were going smoothly when the six-up evener broke at the pin. The metal evener slammed into the hocks of my mules and they jumped right into the metal eveners of the team in front. Fortunately they all stopped, as mules do, and let us help them without panicking and causing more injury to themselves. I had a bit of doctoring to do but they would all be back to work in the morning. I started personally checking all this old equipment each day before hitching any mules to it as did Luke and Gene. By now our camp had grown fairly large, I’m guessing close to fifty total. We assigned each team of six to one person and he recruited helpers from the 20 some teamsters that showed up to help. The goal was to recreate an old time harvest camp and that’s exactly what we had become, working from sunup to sundown. Every evening there were chores to do, from trimming hoofs to repairing harness. We were constantly repairing harness. Fact is we had a repair shop set up under a large oak tree. Everybody pitched in to help and the camp cooks kept us well fed. After dark a few of us would gather for a cocktail and a story or two then we would hit the bunks exhausted. We had become more than a camp we had become a community. By Thursday we were running out of time but fortunately all the remaining mules were fairly bomb proof except for Norms bay mule, Lucy, who had never been in harness before. Just in case we needed an extra, we decided to give Lucy a crash course on the training cart with 5 other well broke mules. She managed to knock down three men before we even got her hitched and then the real rodeo was on. So far I liked Lucy because she made Buckwheat look like a real gentleman. Down the field we went with Lucy doing her best to break free, she was right on the verge of hurting herself when she just stopped her rebellion and walked out like she belonged there. We traveled a short distance before she again threw another fit this time giving in a little quicker. Gene advised us that she would probably try one more time and sure enough he was right. After that third try of rebellion, she accepted her new job. That was all the time we had to spare on a mule we didn’t intend to use any way. The storm had cost us a day and a half and we only had 26 mules on the harvester. We planned to get an early start Friday morning, adding our last team of 6 right before our first show. It was show time and all 32 mules were in position, the truck was still anchored to the back of the harvester, and out walkers had lead ropes on all the mules on the outside of the hitch. We not only had to worry about our safety but now there were several hundred spectators to worry about. George climbed the Jacobs Ladder, a platform high above the wheel team; from there he would drive the two leaders using 90 foot lines. We had lines to the six wheelers along with the swing team in front of them; I would drive these mules from my position at the base of the ladder using the bottom rung as a seat. From here I could hold them back somewhat and help with the 90 degree turns we planned to make. Luke led the leaders forward stretching the fifth chain tight then George called “Molly” and we were off. The machine makes a terrible whine and the wheelers and swing team about pulled my arms out of their sockets but after a few yards I was able to get them collected. Everything was lining out well but then we had to stop for adjustments. We no sooner got started again and we had to stop because the machine broke. A quick repair and off we went again. Each time we started it got harder for the leaders to start the whole hitch; it was evident that we needed a third mule to help the lead team. A glance at the picket line showed one lonely mule left standing there, Lucy. We moved another broke mule forward and replaced her with Lucy. She made a big commotion for a while but finally resigned to the fact that this was her job to do. Soon we felt we could trust the mules so the truck was unchained from the back of the Combine and soon the out walkers unsnapped their lead ropes and stepped aside. We were now a working 33 mule hitch. One of the show organizers did some research and informed us that this was the first time since 1934 that a 32 mule hitch has been used and we just broke our own record with 33. Saturday morning went much smoother. Gene drove from the top of the Jacobs Ladder while Luke trained Wes to do his job up front. We were once again plagued by equipment problems and made several stops but the Harvester crew worked on the machine all thru lunch break and informed us it was ready to go. After lunch George and Gene stood off to the side, it was time to hand the lines to the next generation. They had preserved this art as long as possible and made a tremendous effort to pass it on. It was up to us to keep it going. Luke climbed the ladder and smiled down at me with a gleam in his eye. “Are you ready for this?” he asked. “I’ve been ready since you called last August,” I replied. A nod to Wes and he led the leaders forward till the fifth chain was tight and straight. “Molly” Luke hollered and we made the smoothest start yet. At the first turn Luke started to swing the leaders right and all the teams fell in, I held my wheelers and swing team straight until the combine reached the end of the stand of grain then let the swing team fallow while holding the wheelers in the turn. A perfect turn and we were lined back out heading across the bottom of the field. We had so much trouble before I kept expecting to have to stop. We reached the end of the field and executed another perfect turn; then another. The sackers riding the harvester were working their butts off keeping up with the grain coming down the chute. Our last turn we pivoted that machine on a dime and headed back to where we started, a full trip around the field without a stop. What a great feeling of success. Sundays show was again hampered by equipment problems and we finally had to shut the machine down all together. At a hundred and six years old you have to expect some break downs. Doesn’t matter, we had our triumph. Hopefully we’ll get another chance to make history in the future. The mules that will be placed in the exhibit are here and waiting for construction to be completed before they are hitched to the wagons. A boardwalk is being installed to help cut down on the dust stirred up by walking through the building. The finishing touches are being completed.

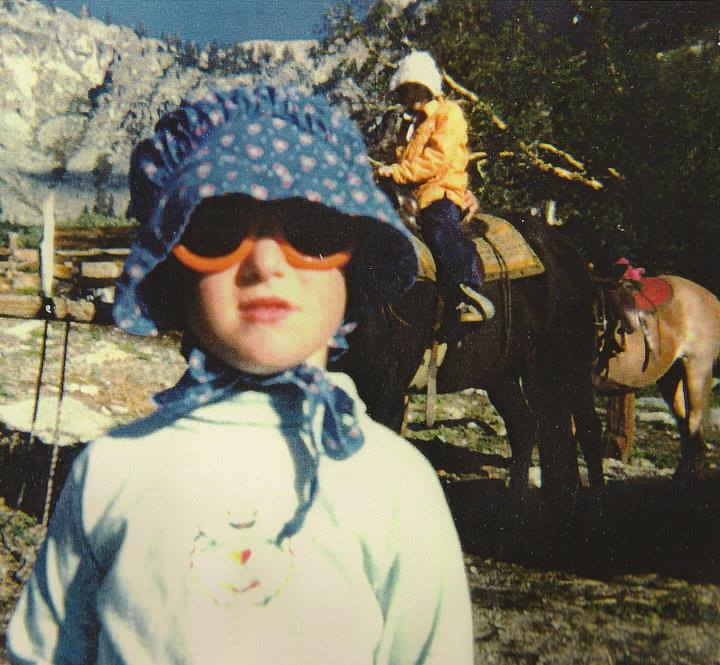

Holly at about age 6, about to ride out of Onion Valley to Charlotte Lake. The American Mule Museum has a new newsletter editor and she has also recently joined the Board of Directors. Holly Subia is a fitting addition to the AMM: She grew up in Bishop California as Holly Nash and spent most of her summers in the high country of the Sierra Nevada. Her first job was at Rainbow Pack Outfit where Mark Berry and crew taught her about working stock in the Eastern Sierra. Holly got the bug and spent most summers packing mules at various pack stations on the east and west side of the Sierra Nevada and spent five seasons in Yosemite as a mounted back county ranger. She has recently returned to living in the Eastern Sierra and has joined some old friends and made some new friends that are enthusiastic about mules. She looks forward to sharing her love of mules by working with the AMM and helping everyone appreciate all that mules have done for us, here in the Eastern Sierra and beyond.

|

AuthorAmerican Mule Museum: Telling the story of How the West Was Built – One Mule at a Time Archives

January 2021

Categories |